By Daphene R. McFerren

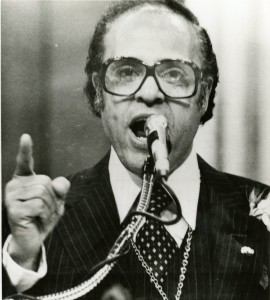

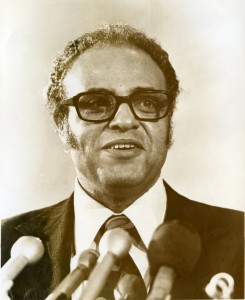

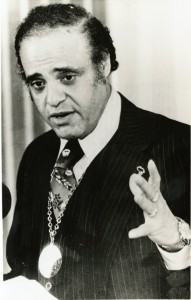

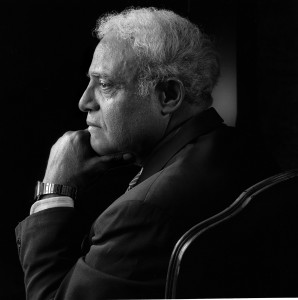

Duty of the Hour, a film on civil rights activist and native Memphian Benjamin L. Hooks, encourages us to ask ourselves, “To what extent are our lives today in the service of advancing a higher good for others?” The documentary chronicles the struggle for civil rights in Memphis and the nation during the 1960s and 1970s through the life of Benjamin Hooks. Hooks’ story demonstrates that civil rights activism is an undertaking not for the weak of heart, but instead a demanding endeavor requiring strong character; an ability to take, and move on from, harsh criticism; strong prayers; and a sense of optimism that universe is on your side.

Benjamin L Hooks and other civil rights activists of the 1960s were under no illusions that the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s would fix hundreds of years of discriminatory practices against African Americans. While they were encouraged by gains of the Civil Rights Movement, they nonetheless remained deeply concerned about the impact of entrenched poverty and racism in American society. “The Poor People’s Campaign,” Dr. Martin Luther King’s grand scale initiative to tackle poverty in America, illustrated the pervasiveness of economic disparities even in the 1960s. Today, as well as then, poverty locks a disproportionate number of African Americans and others in a cycle of economic despair, preventing self-determination and full participation in the life of the community and nation.

CONTINUING THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT IN TODAY’S WORLD

While clearly not our “mothers’ and fathers’ Civil Rights Movement,” in many respects the #BlackLivesMatter movement picks up where the Civil Rights Movement left off. The issue of policing in minority communities and the shocking deaths of young African American men in the last few years at the hands of the police, or in the case the death of Trayvon Martin, by a self-pointed vigilante, have rocked African American communities to their core. While #BlackLivesMatter’s most prominent issue has been excessive use, or unnecessary use, of deadly force by the police against African Americans, the movement has begun to challenge systemic issues of poverty, unemployment, and discrimination impacting African Americans. Much like the movement’s predecessors, #BlackLivesMatter challenges the strong fibers of racial inequality that run through the fabric of our nation.

As Duty of the Hour unfolds, it’s clear that Hooks, Democrats, and Republicans, worked to build bridges to ensure more inclusive and just communities. Here too is a lesson’s for today’s leaders. While Duty of the Hour is a historical account of past events, it is also a mirror for self-examination by each of us about our “duty” to create fair and just communities for African Americans, the poor, and others in today’s world. Like the 1960s, the struggles of our time require thoughtful examination, reflection, and action within the spheres of our influence.

While much work remains to be done, Hooks and civil rights activist of his time made it across the bridge to create a more just, but still imperfect, nation. We too have a bridge to cross. Our nation faces a crisis with respect to disproportionate incarceration rates for African Americans, entrenched poverty of both black and whites, and severe class and wealth differences that negatively impact us all. These pressing issues clearly show that we have a rough, unsteady, and difficult bridge to cross. Some, including #BlackLivesMatter, activists, and concerned others have begun the walk over the bridge. Making it across this bridge will not be easy. But again, as history makes clear, it never has been.

THE STORY OF BENJAMIN L. HOOKS

The trajectory of Benjamin L. Hooks’ life, and his impact on Memphis and the nation, could not have been fathomed at the time of his birth. Hooks was born in Memphis in 1925, a time when Jim Crow laws openly condoned segregationist and racist practices. Hooks attended LeMoyne College, now LeMoyne-Owen, and completed law school, aided in large part by the benefits he received from GI bill while serving in World War II. During the war, Hooks realized that the Italian prisoners of war whom he guarded enjoyed greater privileges as white prisoners than Hooks held as a soldier serving his country. Like other African American veterans of World War II, Hooks returned to America a changed man with a resolve to fight racial inequality.

In 1965, former Tennessee Governor Frank G. Clement appointed Hooks to serve as a criminal court judge in Memphis, making Hooks the first African American judge in a court of record in Tennessee’s history. While this appointment was life changing for Hooks, it proved to be a brave and courageous move for a white governor who, by the very act of appointing Hooks, unleashed a fury of hate upon himself from whites and members of the voluntary bar association of Memphis.

Hooks was appointed by to the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) by President Richard Nixon in 1972. There Hooks fought to protect First Amendment rights even in cases such speech was racially offensive. While at the FCC Hooks worked to increase minority ownership of broadcast media to ensure a diversity of voices in broadcast media.

In 1977, when Hooks became the director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Hooks held a national stage where he could advance a civil rights agenda that included combatting poverty, creating jobs and business opportunities for African Americans, and ending apartheid in South Africa. Even after retiring from the NAACP in 1992, Hooks remained a lifetime advocate for racial equality and emphasized the urgent need for African Americans to play a pivotal role in economic life of this country.

Duty of the Hour premieres on WKNO Monday, September 12, 2016 at 7 PM; and again on WKNO-2 Tuesday, September 12, 2016 at 7 PM. To learn more about the film and the Hooks Institute, please visit www.memphis.edu/benhooks or www.memphis.edu/dutyofthehour

About the Author

Daphene R. McFerren is the executive director of the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change. McFerren manages the Hooks Institute’s strategic planning; program creation and implementation; local and national fundraising efforts; and work on behalf of the Hooks Institute staff, faculty, and contractors. McFerren is responsible for creating budgets for Hooks Institute programs and monitoring program expenses to ensure that financial targets are met. She is the primary media contact for the Hooks Institute and has made numerous television and radio appearances to promote its work. McFerren was the executive producer of the film Duty of the Hour, a film about the life of Dr. Benjamin L. Hooks.

Daphene R. McFerren is the executive director of the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change. McFerren manages the Hooks Institute’s strategic planning; program creation and implementation; local and national fundraising efforts; and work on behalf of the Hooks Institute staff, faculty, and contractors. McFerren is responsible for creating budgets for Hooks Institute programs and monitoring program expenses to ensure that financial targets are met. She is the primary media contact for the Hooks Institute and has made numerous television and radio appearances to promote its work. McFerren was the executive producer of the film Duty of the Hour, a film about the life of Dr. Benjamin L. Hooks.