By: Will Love

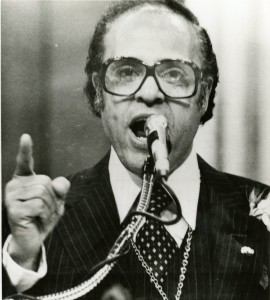

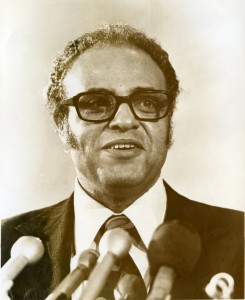

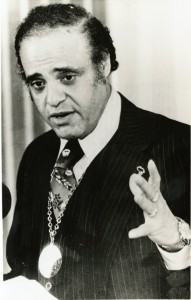

Housed in the Preservation and Special Collections Department of the University of Memphis Libraries are the Benjamin Lawson Hooks Papers (MSS 445). By far one of the most expansive holdings of Special Collections, the Hooks papers span close to 400 boxes, containing correspondence, speeches, printed materials, administrative files, photographs, and audio and video recordings that pertain to the life of Benjamin Hooks, long time lawyer/civil rights activist and executive director of the NAACP from 1977-1992.

As a recently hired staff member of the University of Memphis Libraries, I have begun the process of digitizing major components of the Ben Hooks papers, a project sponsored by the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change. So far, I have focused on the scanning and recording of the photograph and audio-cassette portions of the collection. With roughly 1200 photographs and several dozen hours of audio files, the Hooks Institute, the University of Memphis Library, and I aim to make a significant sample of images and audio recordings available online for public access. As we continue to build the Hooks digitization project website, we will also include a representative sample of scanned manuscripts to supplement the photographs and audio series. Our aim is to demonstrate the richness of the Hooks collection so that scholars and engaged members of the public visit the Preservation and Special Collections Department to research the Hooks papers more fully.

The majority of the collection pertains to Hooks’ time as executive director of the NAACP from 1977-1992, as these years comprise over 90 percent of the collection. As director, Ben Hooks gave many public speeches both to and on behalf of the NAACP, where he outlined his disagreements with the policies of President Ronald Reagan and Hooks’ concerns with the general socio-economic direction of the country.

In conjunction, Hooks also served as pastor-on-leave of Mt. Moriah Baptist church in Detroit, Michigan where he on occasion preached both to Mt. Moriah and other churches and assemblies around the country. Hooks felt the call to ministry in his youth and was ordained as a Baptist minister in the 1950s, preaching regularly for the Greater Middle Baptist Church in Memphis before becoming a pastor in Detroit in the 1970s.

Having read through many of Hooks’ speeches and listened to many recorded sermons, one immediate observation stands out: Hooks gives an interesting look into a life of racial equality advocacy before the age of social media but after many initiatives of the 1960s civil rights era had been achieved.

In his sermons, Hooks was fond of quoting Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” as Hooks believed that this quotation described the life of African Americans in the 1980s. On the one hand, Hooks was clear that African Americans had made substantial progress in the last two decades, thanks to the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. African Americans had cumulatively earned enough wealth that if they consolidated and implemented it in a focused direction, they would carry enough influence to bring even the biggest corporation to its knees. African Americans were now mayors, police officers, judges, and business owners in numbers unprecedented in American History.

On the other hand, Hooks believed that the African American community was in a greater crisis now than any other time in history. He often made pointed jokes of African Americans “tithing to the local liquor store” and stark remarks about the level of violence prevalent in many African American neighborhoods, noting that the number of African American men murdered by other other African American men was far greater than the number of African American men lynched in the early twentieth-century South. The remedy for this problem was not government intervention (though Hooks as NAACP director tirelessly advocated for the prolonging of targeted programs) but rather a revival within the African American community, centered on the church and the family.

Hooks, thus, demonstrates the changing nature of rhetoric throughout the history of civil rights. Hooks, at times, sounds like an affirmative action minded civil rights activist, calling Reagan and other conservatives to task over slashing publicly funded programs designed to create opportunities for the poor. In Hooks’ view, Reagan’s policies would not engender equal prosperity for all Americans but in fact, stimulate wealth redistribution from the poor to the rich, destroying the progress achieved over the last two decades. At other times, Hooks sounds like a modern social conservative, noting the central role of the church, the family, and the responsibility of the individual to correct his or her own problems, regardless of prevailing societal ills.

Much of Hooks’ mixed messaging can be attributed to varying audiences. When preaching to a predominantly African American congregation, he sounds quite differently than when speaking to a national audience on behalf of the NAACP. But, I suspect, much of it also stems from a time period when an individual as prominent as Hooks could easily find a media platform for his initiatives without worrying over the “viral” tendencies of today’s hyper charged social media exchanges. Hooks could craft political messages and rhetorical strategies designed to make the nightly news and morning newspapers without worry that a misinterpreted statement would spread around the internet in moments. In this regard, Hooks’ tenure with the NAACP represents a transitional moment in the history of the civil rights movement, and while it shares many differences with our current struggles, it perhaps has more in common with our own struggles than did the marches and protests of the 1960s.

All photographs pictured are the property of Special Collections, the University of Memphis Libraries.