Race, Representation, and Photography in 19th Century Memphis: from Slavery to Jim Crow, is an in-depth study of African American visual culture and history. Using Victorian era photographs, pictorial illustrations, and engravings from local and national archives, I examine intersections of race and image within the context of early African American community building. The city of Memphis serves as the case study, wherein black agency and photographic images intersect to reveal the hidden history of racialized experiences in the urban south during slavery and freedom following the Civil War. My interdisciplinary research links the social history of photography with the fields of art history, visual culture, critical race studies, gender, and southern studies.

Race, Representation, and Photography in 19th Century Memphis: from Slavery to Jim Crow, is an in-depth study of African American visual culture and history. Using Victorian era photographs, pictorial illustrations, and engravings from local and national archives, I examine intersections of race and image within the context of early African American community building. The city of Memphis serves as the case study, wherein black agency and photographic images intersect to reveal the hidden history of racialized experiences in the urban south during slavery and freedom following the Civil War. My interdisciplinary research links the social history of photography with the fields of art history, visual culture, critical race studies, gender, and southern studies.

I was inspired by Frederick Douglas, black abolitionist, and pioneering intellectual of the nineteenth-century. Douglas, as the most photographed celebrity of the era, understood the influence of the new visual media to impact people’s thinking. At the height of the Civil War Douglas began to write and lecture about the potential of photography to transform society. He argued that the new technology offered former slaves the power they sought to represent themselves the way they wanted to be seen; with dignity and control over their own lives as free human beings.

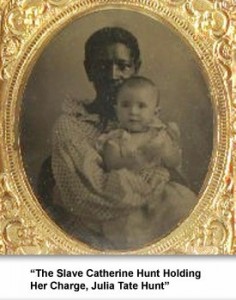

The book begins with the story of the slave trade, urban slavery, and the Civil War, telling stories from the perspectives of the enslaved in Memphis. Rare photographs of Catherine Hunt, enslaved as a nursemaid in the Driver-Hunt Phelan antebellum mansion located on Beale Street, enabled the author to focus on the experiences of black women. A tintype of a young teenager named ‘Harry,” owned by one of the largest slave-owners in the region, John Trigg, allowed me to tell the story of freedom through his eyes. A picture of women, men, and children in an area contraband camp helped to tell the story of the thousands who escaped slavery on rural plantations to seek refuge in Union occupied Memphis. By the end of the war the black population in Memphis had swelled to over 16,000.

During Reconstruction freed people in Memphis organized benevolent societies, and shared resources in order to establish churches, schools, businesses, and cemeteries to bury their dead. They secured jobs as “clergyman; brick-molder; farmer; build cisterns; mattress-maker; lumberyard; physician; drayman; grocery keeper; teamster; laborer; fireman; painter; carpenter; coachman; lamp lighter; machinist; steamboat foreman; brickmason; saloon keeper; cotton planter; stock driver; picks cotton; bartender; whitewasher; gardener; foundry molder; hatter; cooper; waiter; cupola-man’ stonecutter; brakeman; sailor; broom maker; and mail gatherer.”

Sacred institutions like ‘Mother Beale,’ Collins Chapel, and Avery Chapel, were among the first churches freed people constructed. They survive to this day. The freedmen school first established as Lincoln Chapel in Camp Shiloh grew into LeMoyne Normal Institute, and finally LeMoyne Owen College. And in 1877 Zion Cemetery was established as a beautiful, park like resting place of fifteen acres along South Parkway in the suburbs of Memphis.

By the 1880s Memphis was a thriving black community with social, educational, and commercial opportunities associated with the excitement of urban living. Although the specter of Jim Crow was looming and political rights eroding, African American leaders held on to political offices through the 1880s. Lymus Wallace served on the city council between 1885 and 1891; Josiah T. Settle became the first assistant attorney general in 1885, and Ed Shaw was wharf master during the early 1880s. Isaac F. Norris and Thomas Cassells were elected to the Tennessee state legislature in 1881. Entrepreneur Robert Church Sr. continued his rise to prominence by expanding his assets in saloons, hotels, and real estate.

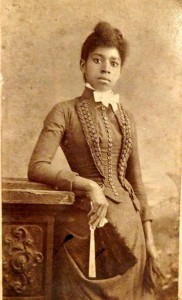

Women like Catherine Hunt remained in Memphis, working as a laundress all her life. She joined Beale Street Baptist Church and was a member of the church organization that established Zion Cemetery, where she was buried in 1899. She had the foresight to leave a will, and the few hundred dollars Catherine managed to save was bequeathed to relatives more poor than she. Numerous black women supported their families as seamstresses like Jane Wright, and teachers like Julia Hooks, Virginia Broughton, and Ida B. Wells. The book includes a number of extraordinary photographs representative of black social life in Memphis within the broader context of the Victorian era.

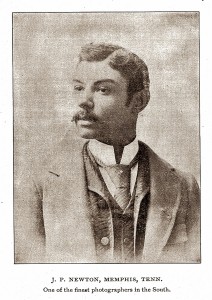

James P. Newton, the first professional black photographer in Memphis opened his studio in 1897on Beale Street, by then the epicenter of the early black community. Photographer-entrepreneurs like Newton, would play an important role in combatting race in America. By the turn of 20th century, scholars like W.E. Dubois were at the vanguard of attacking racial stereotypes, formulating his ideas in theory and practice, into a movement that came to be known as the ‘New Negro.’ Black photographers provided them with the visual weapons, as evidence, to do so, documenting everyday life, and aspirations in the communities to which they also belonged. Their pictures of black beauty, pride, ambition, and success were disseminated in black newspapers, books, journals, and magazines across the nation, and in world fairs and expos abroad in Europe. A mesmerizing visual record of African American history, these early photographs today, inspire contemporary artists in all media. The spoken and written words of Frederick Douglas proved indeed, to be prophetic.

About the Author

Earnestine Jenkins is Professor of Art History in the Department of Art at the University of Memphis.She teaches courses in African American and African Diaspora arts and visual culture. Her areas of research include early African American photographic history, the study of the African diaspora in Europe focused on the relationship between the arts, slavery, colonialism and empire; 19th century Ethiopian manuscripts, African Diaspora cinema, Gender Studies, and the history of blacks in the urban south.