By: Nathaniel C. Ball

September 30, 2015

Thomas Moss symbolized the urban entrepreneurial class of African Americans that emerged in the decades following the Civil War. Moss invested in a community-owned grocery store, the People’s Grocery, which he managed at night after spending his days working as a postman. The People’s Grocery was located at the southeast corner of what is today Mississippi Blvd and Walker Ave, known then as “the Curve” for the distinctive turn that streetcars made at the corner. During an era in which African Americans were subject to racial subjugation, the People’s Grocery stood as an emblem of pride for the community.

William Barrett, a white man and proprietor of a rival store in the area, felt economically threatened by the People’s Grocery. After he was injured in a scuffle that took place in the Curve on 2 March 1892, Barrett determined to use the incident to discredit Moss’s establishment. Barrett blamed his injuries on a young worker at the People’s Grocery, William Stewart. Barrett arrived at the People’s Grocery the next day with a police officer to arrest Stewart. Instead, Barrett and the officer were met by Calvin McDowell, a grocery clerk, who refused to give up his co-worker’s location. Furious, Barrett struck McDowell with a revolver, losing his grip in the process. McDowell’s athleticism got the better of Barrett. McDowell grabbed the fallen revolver and shot at Barrett, barely missing him. Barrett and the officer retreated. McDowell remarked in the Appeal-Avalanche, “Being the stronger, I got the best of the scrimmage.” This statement only fueled Barrett’s anger. Subsequently, Barrett notified the authorities of the incident. Within a few days Barrett was deputized by a Shelby County Court judge, with permission to form a group to get revenge on those who offended him at the People’s Grocery.

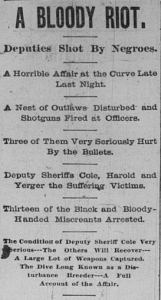

Well aware that an attack was imminent, the patrons of the People’s Grocery asked local authorities for protection. The city of Memphis refused, as the Curve was located just outside of the city, thus outside their jurisdiction. Faced with no other option, a group of men armed themselves inside the People’s Grocery. On Saturday, March 5, Barrett and his men marched towards the Curve. A gunfight ensued in which three of Barrett’s men were injured.

The Memphis Commercial and the Appeal Avalanche inaccurately characterized the attack as evidence that the African American tenants of the People’s Grocery were planning a race war against whites, when in fact those inside the People’s Grocery were simply defending their establishment from attack. Though no evidence suggested Moss was involved in any of these events, his position at the People’s Grocery led the white owned newspapers to sensationalize his name, claiming he was the leader of a great “black conspiracy” against whites. White mobs stormed the Curve damaging property while searching for Moss, McDowell, and Stewart. The three men quickly turned themselves in to prevent any other harm to their community and were held at the Shelby County Jail as they awaited trial. After a few days, the frenzy surrounding the case died down, and security around the prison was lessened.

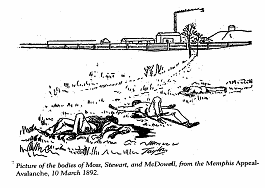

On 9 March 1892 at around 2:30 A.M., 75 masked men stormed the Shelby County Jail and forcibly removed Moss, McDowell, and Stewart. The three men were taken a mile north of the city, where they were mutilated and murdered. The description of the lynching in the Appeal-Avalanche and the Memphis Commercial the next morning is chillingly positive, a troubling aspect to the city’s reaction to the murders.

“There was no hooping, no loud talking, in fact, nothing boisterous. Everything was done decently and in order… The vengeance was sharp, swift, and sure but administered with due regard due to the fact that people were asleep all around the jail. [They] did not know until the morning that the avengers swooped down last night and sent the murderous souls of the ring leaders in the Curve riot to eternity.”

9 March 1892, Memphis Appeal-Avalanche

The article gives a description of the brutal attacks conducted by the mob on the three African American men in such detail that one could identify each victim by the wounds inflicted on the bodies of Moss, McDowell, and Stewart when they were found the next morning. Even Moss’s last words were recorded, with an urgent plea to the African American community of Memphis, “Tell my people to go West, there is no justice here.” A call that many in the African American community would follow in the coming decades. The next day a mob ransacked the People’s Grocery, and the store was closed. Within a few months Barrett bought the establishment for pennies on the dollar.

“Thus, with the aid of the city and country authorities and the daily papers, that white grocer had indeed put an end to his rival Negro grocer as well as to his business.”

Ida B. Wells Crusade for Justice

Like other lynchings in the United States at the time, the Memphis lynching stood as a warning to African Americans that pushed against the American South’s racial hierarchy. Moss was murdered for running a better business than his white competitor; McDowell, for forgetting his place in the hierarchy of the white world he lived in; and Stewart, for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. While many would back down when faced with these threats of violence, Ida B. Wells, an emerging journalist in Memphis at the time and personal friend of Thomas Moss, fearlessly attacked those who participated in, encouraged, or simply ignored the lynching. Her unrelenting attacks would eventually lead to her exile from Memphis, the place she had called home for nearly a decade.

A finer, cleaner man than he never walked the streets of Memphis. He was well liked, a favorite with everybody; yet he was murdered with no more consideration than if he had been a dog… The colored people feel that every white man in Memphis who consented in his death is as guilty as those who fired the guns which took his life.”

Ida B. Wells on Moss death, Crusade for Justice

Today, the story of the People’s Grocery is marked by a single historical marker, just west of Lemoyne-Owen College, where the co-op once stood. As the Hooks Institute moves forward with our documentary film on the Memphis experience of Ida B. Wells, it is important to remember that these events happened in our backyard, to real people with their own hopes, desires, and dreams. The Hooks Institute aspires to tell these stories, and others like it, with the respect they deserve.