By Errol Rivers

Beginning in 2015, I have worked as a graduate assistant at the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change. I have primarily worked as an editor and proofreader on an archival project referred to as the Civil Rights Movement of Fayette County, Tennessee (1959–mid-1970s). This collection of documents, stories, photographs, and correspondences chronicles the challenges African Americans in Fayette County faced while fighting for the right to vote and other basic civil rights. Activist efforts included organizing to access their right to vote in elections, developing strategies to acquire shelter and necessities after white landowners forced African-American sharecroppers out of their homes to live in tents, and advocating for the desegregation of schools in Fayette County, among other things. Together, the various printed and electronic features of this collection capture specific characteristics of grassroots activism in the South during a time of intense racial and socioeconomic strife.

My work with the Hooks Institute began at a critical juncture in my life. In 2015, social media and the news were rife with examples of police brutality and other injustices against marginalized groups. I had become overwhelmed with a sense of powerlessness in response to the wide circulation of audio and video footage depicting graphic violations of civil rights—especially that involving deadly interactions that occurred between law enforcement and black women, men, and children. Beyond my personal stakes in the welfare of minority groups, I, along with many of various backgrounds, seemed to be growing both anxious by and weary of hearing about the emotionally charged topic of injustice. Having been raised several decades after the Civil Rights Movement, I expected the distanced experience I had always enjoyed when studying past civil rights history would, unfortunately, feel far more immersive in such a socially turbulent time for minority groups. As I spoke with family and friends about the work I would soon begin, they, too, were concerned about my emersion into history about past abuses African Americans suffered in Fayette County when I needed to look no further than recent news for current instances of oppression. However, as I began my work at the Hooks Institute, this fear of sinking further into hopelessness was replaced by a passionate commitment to the change I might help to create. This change in perspective was thanks to the inspirational story of the Civil Rights Movement of Fayette County.

It would be easy to reduce my time learning about the movement in Fayette County to a lesson in dates, Martin Luther King Jr’s impact, and the unjust yet historic nature of the time—this narrative is certainly a familiar focus of many educational materials on the 1960s. However, what I found to be powerful, unique, and transformative about the collection was its emphasis on the lived experiences of those who stood up, against the odds, to demand respect for themselves and their constitutional rights. The collection was also unique because it allowed the viewer, through first-hand accounts of the activists, to experience past events in “real time,” to examine how activists felt as events took place. This collection allowed me to go beyond written facts to the “spirit” of ordinary people, who became extraordinary activists in pursuit of equality.

Particularly moving is the collection’s tangible expansion of what defines a true leader. When I learned about the American Civil Rights Movement as a child, civil rights heroes appeared so powerfully eloquent, strategically well dressed, and justifiably revered. Their colossal images shrunk my belief that I could ever do or change anything like they did. What the collection offered me was the insightful perspective that leaders take many forms: leaders include the faces, voices, and bodies of the poor, rural South.

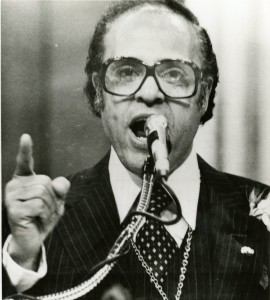

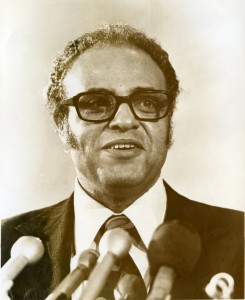

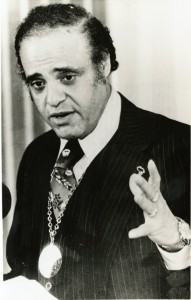

The riveting personal stories and specific details depicted in the collection’s photographs, video clips, and written correspondences offer a unique and boldly honest depiction of Southern activism, as told by various Fayette Countians and Northern allies. Rich, emotionally-complex stories of persistence, sacrifice, and conflicted morality are found in the accounts of those of local leaders, like John McFerren and Harpman Jameson, World War II veterans who provided the early leadership to voter registration efforts; Maggie Mae Horton, an “aggressive” activist who worked to create solidarity among African Americans in her voting district; and Northern civil rights workers who volunteered their time, resources, and like local activists, risked their safety to demand civil rights for African Americans. These and similarly interesting stories demonstrate why the Fayette County movement is so inspirational. In this way, the collection adds to a necessary space in recorded history for black, rural Southerners of the time, whose stories have too often gone untold to the extents that they deserve.

As the civil rights issues described in my work unavoidably infiltrated all parts of my personal life during the campaigning season of the 2016 presidential election, I, like many Americans, felt compelled to reevaluate my understandings of civic duty, leadership, and the self. This would be necessary as I decided how I might orient myself within such a divisive moment in United States history. For guidance, I looked to the courageous individuals who came before me, and they exemplified one thing about change: silence was—and is—no option when in the face of injustice. Journalist and civil and women’s rights activist Ida B. Wells once said, “The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.” Author Zora Neale Hurston warned, “If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.” Wells and Hurston demanded personal responsibility to fight injustices.

While many might believe they can surrender their voice and political agency to a single more charismatic, visible, or wealthy “leader,” the events that unfolded in Fayette County show that ordinary people of all backgrounds can, and have taken, courageous and strategic action to resist discrimination. Of course, we each have limits to our ability and reach, but activism, monumental and small, is the burden and the privilege that everyday people can carry to help ensure the welfare of others.

How, though, do we carry this burden and honor the opportunities our rights afford us? In Fayette County, local African American leaders created the Original Fayette County Welfare League to empower African Americans by helping them to register to vote and creating literacy schools, among other things. In our current cultural moment and everyday lives, everyday activism may look like engaging in difficult conversations about privilege, learning about and attending a protest, diversifying the required readings on a syllabus for an upcoming course, or working to challenge our own biases through committed education. However we define our activist efforts, I have come to believe that committing to personal growth and using our platforms and privileges to create positive change is how our roles as citizens, leaders, and everyday people intersect in the achievable ideal.

Throughout history, the promise of change seemed to flow from an (im)perfect storm of social and economic upheaval. Through these unique moments in time, our greatest progress in furthering civil rights and social justice have taken place. Since I began working with the Hooks Institute, the turbulent social and political landscape of which I was previously afraid has only intensified as we have struggled to engage with one another to discuss issues, such as race relations, gender equality, immigration, gender identity, environmental justice, and many more. Despite this, I—and I hope many in the nation—believe it is imperative to work actively towards a renewed, spirited and tenacious sense of unity to effect meaningful, positive change for each and every one of us. My exploration of the civil rights movement in Fayette County allowed me to situate myself and today’s social and institutional struggles within a legacy of unified and effective resistance to injustice in our nation. This could only occur because, through the collection, it was easy to see, if not myself or a loved one in the faces and stories portrayed, the universal humanity in the textured voices and strong familial ties featured in the collection.

Although I lack answers as to how I, you, or we might do so, the accomplishments of the Civil Rights Movement of Fayette County make it undoubtedly clear that an ability to persist through adversity exists in each of us. As such, I have come to believe that, through our thoughtful, everyday acts of activism, we work to cultivate a world that, rather than drains, invigorates us to want to persist for the call of social justice, regardless of the circumstances thrust upon us.

The Civil Rights Movement of Fayette County collection is in no small part a creation of a passionate and dedicated collaboration. Several Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change staff members, University of Memphis instructors, staff members of the Preservation and Special Collections Department at the University of Memphis, external scholars, and graduate assistants have devoted a significant amount of time and effort to ensuring the procurement, creation, maintenance, and dissemination of various elements of the project. Additionally, while respectfully crafted and weaved together by Hooks Institute staff and University faculty to present a cohesive narrative, little to none of the collection would exist without the tremendous support of the people of Fayette County who volunteered their time to help tell their stories. This extraordinary example of collaborative writing, community engagement, and committed scholarship stands as a shining example of the Hooks Institute’s mission of “teaching, studying, and promoting civil rights and social change.”

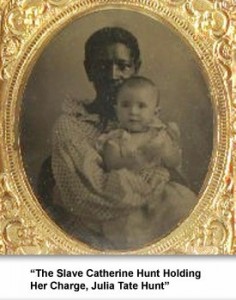

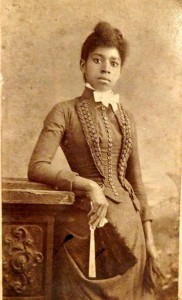

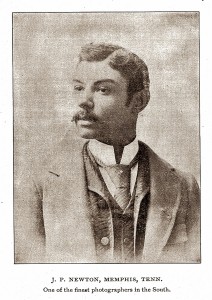

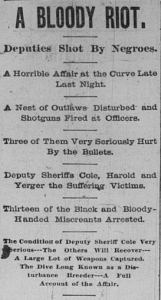

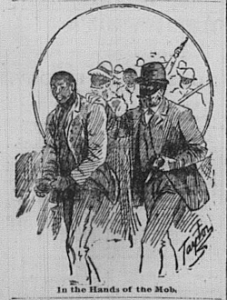

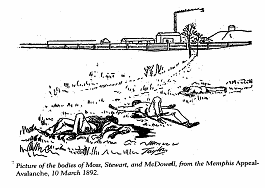

Race, Representation, and Photography in 19th Century Memphis: from Slavery to Jim Crow, is an in-depth study of African American visual culture and history. Using Victorian era photographs, pictorial illustrations, and engravings from local and national archives, I examine intersections of race and image within the context of early African American community building. The city of Memphis serves as the case study, wherein black agency and photographic images intersect to reveal the hidden history of racialized experiences in the urban south during slavery and freedom following the Civil War. My interdisciplinary research links the social history of photography with the fields of art history, visual culture, critical race studies, gender, and southern studies.

Race, Representation, and Photography in 19th Century Memphis: from Slavery to Jim Crow, is an in-depth study of African American visual culture and history. Using Victorian era photographs, pictorial illustrations, and engravings from local and national archives, I examine intersections of race and image within the context of early African American community building. The city of Memphis serves as the case study, wherein black agency and photographic images intersect to reveal the hidden history of racialized experiences in the urban south during slavery and freedom following the Civil War. My interdisciplinary research links the social history of photography with the fields of art history, visual culture, critical race studies, gender, and southern studies.