By Khortlan Becton, JD, MTS, The Restorative Education Institute (1)

By Khortlan Becton, JD, MTS, The Restorative Education Institute (1)

This blog post is an excerpt from the 2023 Hooks Institute Policy Papers “The Promise and Peril: Unpacking the Impact of A.I. and Automation on Marginalized Communities.” Read more here.

I. Introduction

From unlocking a phone to identifying shoplifters in real-time, facial recognition technology (“FRT”) use is increasing among private companies and having an increasingly large impact on the public. According to one study, the global FRT market is expected to grow from $3.8 billion in 2020 to $8.5 billion by 2025 (MarketsandMarkets, 2020). Domestically, FRTs are a central aspect of artificial intelligence (“AI”) use and development in the U.S. pri- vate sector. The following statistics demonstrate the growing prevalence of FRT use in the U.S. private sector: 72% of hotel operators are expected to deploy FRTs by 2025 to identify and interact with guests; by 2023, 97% of airports will roll out FRTs; excluding Southwest Airlines, most major US airlines currently use FRTs (Calvello, 2019).

This explosion of private FRT use has prompted many professional organizations and community organizers to call for a moratorium on FRT use until the enactment of state and federal regulatory actions. One such group noted that industry and government have adopted FRTs “ahead of the development of principles and regulations to reliably assure their consistently appropriate and non-prejudicial use” (Association for Computing Machinery [ACM], 2020). Among the stakeholders calling for such moratoriums is a concern over the alarming level of bias present within commercial FRT systems. Given the widespread integration of FRTs throughout society, both presently and to come, the presence of bias in FRTs is particularly troublesome as decision-making driven by biased FRT can lead to significant physical and legal injuries. For example, self-driving cars are more likely to hit dark-skinned pedestrians (Samuel, 2019). Biased FRTs also have the likelihood of producing discriminatory hiring decisions, credit approvals, or mortgage approvals.

Though the observable and conceivable consequences of bias in FRTs are virtually boundless, state and federal regulatory schemes have not adapted to the growth of FRTs. A continuing lag in regulations designed to address bias in FRTs will likely lead to a range of discriminatory effects that existing agencies do not have the capacity to prevent or redress. Therefore, a federal regulatory scheme propagated by a new agency specifically authorized to regulate AI technologies will better ensure the governance of private entities’ use of facial recognition technologies to address bias than the current regulatory scheme.

A. The Relationship Between AI and FRTs

In popular usage, AI refers to the ability of a computer or machine to mimic the capabilities of the human mind and combining these and other capabilities to perform functions a human might perform (IBM, 2020). AI-powered machines are usually classified into two groups—general and narrow (Towards Data Science, 2018). Narrow AI, which drives most of the AI that surrounds us today, is trained and focused to perform specific tasks. (IBM, 2020). General AI is AI that more fully replicates the autonomy of the human brain—AI that can solve many types of problems and even choose the problems it wants to solve without human intervention (IBM, 2020).

Machine learning is a subset of AI application that enables an application to progressively reprogram itself, digesting data input by human users, to perform the specific task the application is designed to perform with increasingly greater accuracy (IBM, 2020). Deep learning, a subset of machine learning, allows applications to automatically identify the features to be used for classification, without human intervention (IBM, 2020).

Facial recognition technologies are artificial intelligence systems programmed to identify or verify the identity of a person using their face (Thales Group, 2021). “A general statement of the problem of machine recognition of faces can be formulated as follows: given still or video images of a scene, identify or verify one or more persons in the scene using a stored database of faces” (Chellappa et al., 2003). Face recognition is often described as a process that first involves four steps: face detection, face alignment, feature extraction, and face recognition (Brownlee, 2019).

- Face Detection. Locate one or more faces in the image with a bounding box.

- Face Alignment. Normalize the face to be consistent with the database, such as geometry and

- photometrics.

- Feature Extraction. Extract features from the face that can be used for the recognition task.

- Face Recognition. Perform matching of the face against one or more known faces in a prepared database (Brownlee, 2019).

Companies are developing and implementing FRTs in new and potentially beneficial ways, such as: helping news organizations identify celebrities in their coverage of significant events, providing secondary authentication for mobile applications, automatically indexing image and video files for media and entertainment companies, and allowing humanitarian groups to identify and rescue human trafficking victims (Amazon Web Services [AWS], 2021). Recently, FRT has been in the news for its application in the investigation of the Jan. 6, 2021, Capital riot (Sakin, 2021). Other news stories about facial recognition have centered on the coronavirus pandemic. One business proposed creating immunity passports for those who are no longer at risk of contracting or spreading COVID-19 and to use FRTs to identify the immunity passport holder (Sakin, 2021). A MarketsandMarkets (2020) study estimates that the global facial recognition market is expected to grow from $3.8 billion in 2020 to $8.5 billion by 2025.

The Federal Trade Commission’s (“FTC”) recent settlement with Everalbum, a California-based developer of a photo storage app, exemplifies the growth of FRT use in the commercial sector and the liabilities companies may face for implementing the technology. In its complaint, the FTC alleged that Everalbum, which offered an app that allowed users to upload photos and videos to be stored and organized, launched a new feature that, by default, used face recognition to group users’ photos by faces of the people who appear in the photos (Everalbum, Inc., n.d.). Everalbum also allegedly used, without affirmative express consent, users’ uploaded photos to train and develop its own FRT (Everalbum, Inc., n.d.). Regarding its implementation of FRTs, the FTC charged Everalbum

for engaging in unfair or deceptive acts or practices, in violation of Section 5(a) of the Federal Trade Commission Act, by misrepresenting that it was not using facial recognition unless the user enabled it or turned it on (Everal- bum, Inc., n.d.). In January 2021, Everalbum settled the FTC allegations concerning its deceptive use of FRTs. The proposed settlement requires Everalbum to delete all face embeddings the company derived from photos of users who did not give their express consent to their use and any facial recognition models or algorithms developed with users’ photos or videos (Everalbum, Inc., n.d.). The company must also obtain a user’s express consent before using biometric information it collected from the user to create face embeddings or develop FRTs (Everalbum, Inc., n.d.). Everalbum’s recent settlement with the FTC underscores the nascency of federal governance of FRTs, as the Everalbum settlement is among the first of few federal agency enforcements targeting commercial use of FRTs (Federal Trade Commission [FTC], 2019) (2). Signaling the potential for increasing regulation and enforcement in this area, FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra noted that FRT “is fundamentally flawed and reinforces harmful biases” while highlighting the importance of “efforts to enact moratoria or otherwise severely restrict its use” (Federal Trade Commission [FTC], (2021).

B. Bias in Facial Recognition Technologies

Although proponents of FRTs boast high accuracy rates, a growing body of research exposes divergent error rates in FRT use across demographic groups (Najibi, 2020). In the landmark 2018 “Gender Shades” report, MIT and Microsoft researchers applied an intersectional approach to test three commercial gender classification algorithms (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018). The researchers provided skin type annotations for unique subjects in two datasets and built a new facial image dataset that is balanced by gender and skin type (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018). Analysis of the dataset benchmarks revealed that all three algorithms performed the worst on darker-skinned females, with error rates up to 34.7% higher than for lighter-skinned males (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018). The classifiers also performed more effectively on male faces (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018). The researchers suggested that darker skin may not be the only factor responsible for misclassification and that darker skin may instead be highly correlated with facial geometrics or gender presentation standards (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018). Noting that default camera settings are often optimized to better expose lighter skin than darker skin, the researchers concluded that under-and overexposed images lose crucial information making them inaccurate measures of classification within artificial intelligence systems (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018). The report also emphasizes the need for increased diversity of phenotypic and demographic representation in face datasets and algorithmic evaluations since “[i]nclusive benchmark datasets and subgroup accuracy reports will be necessary to increase transparency and accountability in artificial intelligence” (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018).

In 2019, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (“NIST”) released a series of reports on ongoing face recognition vendor tests (“FRVT”). Using both one-to-one verification algorithms and one-to-many identification search algorithms submitted to the FRVT by corporate research and development laboratories and a few universities, the NIST Information Technology Laboratory quantified the accuracy of face recognition algorithms for demographic groups defined by sex, age, and race or country of origin (Natl. Inst. of Stand. & Technol. [NIST], 2018). The NIST used these algorithms with four large datasets of photographs collected in U.S. governmental applications (3) (Natl. Inst. of Stand. & Technol. [NIST], 2018), which allowed researchers to process a total of 18.27 million images of 8.49 million people through 189 mostly commercial algorithms from 99 developers (Natl. Inst. of Stand. & Technol. [NIST], 2018).

The FRVT report confirms that a majority of the face recognition algorithms tested exhibited demographic differentials of various magnitudes in both false negative results (rejecting a correct match) and false positive results (matching to the wrong person) (Crumpler, 2020). In regard to false positives, the NIST found: (1) that false positive rates are highest in West and East African and East Asian people, and lowest in Eastern European individuals (Natl. Inst. of Stand. & Technol. [NIST], 2018) (4), (2) that, with respect to a number of algorithms developed in China, this effect is reversed, with low false positives rates on East Asian faces; (3) that, with respect to domestic law enforcement images, the highest false positive rates are in American Indians, with elevated rates in African American and Asian populations; (4) and that false positives are higher in women than men, and this is consistent across algorithms and datasets (Natl. Inst. of Stand. & Technol. [NIST], 2018). In regard to false negatives, the NIST found: (1) that false negatives are higher in Asian and American Indian people in domestic mugshots; (2) that false negatives are generally higher in people born in Africa and the Caribbean, the effect being stronger in older individuals (5) (Natl. Inst. of Stand. & Technol. [NIST], 2018).

Encouragingly, the NIST concluded that the differences between demographic groups were far lower in algorithms that were more accurate overall (Natl. Inst. of Stand. & Technol. [NIST], 2018). This conclusion signals that as FRTs continue to evolve, the effects of bias can be reduced (Crumpler, 2020). Based on its finding that the algorithms developed in the U.S. performed worse on East Asian faces than did those developed in China, the NIST theorized that the Chinese teams likely used training datasets with greater representation of Asian faces, improving their performance on that group (Natl. Inst. of Stand. & Technol. [NIST], 2018). Thus, the selection of training data used to build algorithmic models appears to be the most important factor in reducing bias (Crumpler, 2020).

Although both the “Gender Shades” and FRVT reports identify under-representative training sets as major sources of algorithmic bias, another recent study of commercial facial algorithms led by Mei Wang showed that “[a]ll algorithms . . . perform the best on Caucasian testing subsets, followed by Indians from Asia, and the worst on Asians and Africans. This is because the learned representations predominately trained on Caucasians will discard useful information for discerning non-Caucasian faces” (Wang, 2019). Furthermore, “[e]ven with balanced training, we see that non-Caucasians still perform more poorly than Caucasians. The reason may be that faces of coloured skins are more difficult to extract and pre-process feature information, especially in dark situations” (Wang, 2019).

Between 2014 and 2018, the accuracy of facial recognition technology has increased 20-fold (Natl. Inst. of Stand. & Technol. [NIST], 2018). However, further applications of FRT will almost certainly bring new challenges if the prevalence of bias remains unchecked. According to Jan Lunter, co-founder and CEO of Innovatrics, facial recognition companies can approach the issue of bias using the insights that the biometrics industry has gained over the past two decades. “Any failure to use these techniques,” Lunter warns, “will not only fan public mistrust, but also inhibit the iterative pace of improvement shown over the past five years” (Natl. Inst. of Stand. & Technol. [NIST], 2018).

II. Current State and Federal Regulatory Schemes

Against a backdrop of scant federal regulation of commercial AI use, including FRTs, several states have adopted their own regulatory schemes to govern the emergent technology. Illinois (740 Ill Comp. Stat), Washington (Wash. Rev. Code), California (Cal. Civ. Code), and Texas (11 Tex. Bus. & Com. Code) have each enacted legislation that targets private sector use of biometric information, including facial images. The states’ legislative schemes commonly define biometric identifiers that encompass facial images by describing them as “face geometry” or unique biological patterns that identify a person (Yeung et al, 2020). However, the states each employ vastly different methods of enforcement. In Texas and Washington, only the state attorney general has enforcement power (11 Tex. Bus. & Com. Code). In California, the state attorney general and the consumer share responsibility for taking action against entities that violate privacy protections (Cal. Civ. Code). While, in Illinois, any person has the right to pursue action against firms and obtain damages between $1,000 and $5,000 per violation (740 Ill. Comp. Stat). Consequently, companies such as Google, Shutterfly, and Facebook have been sued in Illinois for collecting and tagging consumers’ facial information (Yeung et al., 2020).

Facial recognition bans, which range in scope, are on the rise at the municipal level. In September 2020, Portland, Oregon, banned facial recognition use by both public and private entities, including in places of “public accommodation,” such as restaurants, retail stores and public gathering spaces (Metz, 2020). The Portland, Oregon ban does allow private entities’ use of FRTs (1) to the extent necessary to comply with federal, state, or local laws; (2) for user verification purposes to access the user’s own personal or employer-used communication and electronic devices; or (3) in automatic face detection services in social media apps (Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP, 2020). Similarly, Portland, Maine passed an ordinance in November 2020 banning both the city and its departments and officials from “using or authorizing the use of any facial surveillance software on any groups or members of the public” (Heater, 2020). The ordinance allows members of the public to sue if “facial surveillance data is illegally gathered and/or used” (Heater, 2020). Importantly, the Portland, Maine ban does not apply to private companies.

The federal government’s national AI strategy continues to take shape with constant new developments. On November 17, 2020, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (“OMB”), pursuant to Executive Order 13859, issued a memorandum addressed to the heads of executive departments and agencies that provided guidance for the regulation of non-governmental applications of “narrow” or “weak” AI (6) (The White House, 2020). The OMB’s memo briefly recognized the potential issues of bias and discrimination in AI applications and recommended that agencies “consider in a transparent manner the impacts that AI applications may have on discrimination.” Specifically, the OMB recommended that when considering regulatory or non-regulatory approaches related to AI applications, “agencies should consider, in accordance with law, issues of fairness and non-discrimination with respect to outcomes and decision produced by the AI application at issue, as well as whether the AI application at issue may reduce levels of unlawful, unfair, or otherwise unintended discrimination as compared to existing processes.”

Pursuant to the National AI Initiative Act of 2020 (The White House, 2020), the Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy (“OSTP”) formally established the National AI Initiative Office (the “Office”) on January 12, 2021. The Office is responsible for overseeing and implementing a national AI strategy and acting as a central hub for coordination and collaboration for federal agencies and outside stakeholders across government, industry and academia in AI research and policymaking (The White House, 2020). On October 4, 2022, the OSTP released the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights (the “Blueprint”), which “identified five principles that should guide the design, use, and deployment of automated systems to protect the American public in the age of artificial intelligence” (The White House Office of Science and Tech. Policy [OSTP], 2022a).

The five guiding principles are: 1. Safe and Effective Systems; 2. Algorithmic Discrimination Protections; 3. Data Privacy; 4. Notice and Explanation; and 5. Human Alternatives, Consideration, and Fallback.” (The White House Office of Science and Tech. Policy [OSTP], 2022a). The AI Bill of Rights further provides recommendations for designers, developers, and deployers of automated systems to put these guiding principles into practice for more equitable systems. The Biden-Harris administration has also announced progress across the Federal government that has advanced the Blueprint’s guiding principles, including actions from the Department of Labor, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) (The White House Office of Science and Tech. Policy [OSTP], 2022b).

Most recently, U.S. Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer has spearheaded efforts to manage AI by circulating a framework that outlines a proposed regulatory regime for AI technologies. Schumer declared on the Senate floor, “Congress must move quickly. Many AI experts have pointed out that the government must have a role in how this technology enters our lives. Even leaders of the industry say they welcome regulation.” Schumer’s nod towards industry leaders is likely in reference to the several congressional panels that held hearings on AI with industry experts during the week of May 16, 2023. Most notably, Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, the company known for promulgating ChatGPT, testified before a Senate committee on May 16, 2023, imploring legislators to regulate the fast-growing AI industry. Altman proposed a three-point plan for regulation that called for: 1. A new government agency with AI licensing authority, 2. The creation of safety standards and evaluations, and 3. Required independent audits. In response to Altman’s plea, Senator Schumer met with a group of bipartisan legislators to begin drafting comprehensive legislation for AI regulation.

The FTC has already taken an active role in regulating private sector development and use of FRT, as evidenced by its recent settlements with Facebook and Everalbum. Further solidifying the FTC’s regulatory stance, acting FTC Chairwoman Rebecca Kelly Slaughter made remarks at the Future of Privacy Forum specifically tying the FTC’s role in addressing systemic racism to the digital divide, AI and algorithmic decision-making, and FRTs (Federal Trade Commission [FTC], 2019).

On April 19, 2021, the FTC published a blog post announcing the Commission’s intent to bring enforcement actions related to “biased algorithms” under section 5 of the FTC Act, the Fair Credit Reporting Act, and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (Federal Trade Commission [FTC], 2021). Importantly, the statement expressly notes that, “the sale or use of—for example—racially biased algorithms” falls within the scope of the FTC’s prohibition of unfair or deceptive business practices (Federal Trade Commission [FTC], 2021). The FTC also provides guidance on how companies can “do more good than harm” in developing and using AI algorithms by auditing its training data and, if necessary, “limit[ing] where or how [they] use the model;” testing its algorithms for improper bias before and during deployment; employing transparency frameworks and independent standards; and being transparent with consumers and seeking appropriate consent to use consumer data (Federal Trade Commission [FTC], 2021).

III. Argument

The fledgling federal, state, and municipal AI and FRT regulations exist in a loose patchwork that will likely complicate enforcement and compliance for private companies. These complications could hamper or, in some cases, de-incentivize the reduction of bias in FRTs as companies could seek shelter in whichever jurisdiction is most permissive. The federal government’s creation of the National AI Initiative Office does not ensure reductions in FRT bias because the Office is primarily authorized to facilitate AI innovation and cooperation between the government and private companies, rather than addressing any inherent biases present in the FRTs. The FTC’s recent enforcements against private use of FRTs and its recent guidelines indicate that it has an interest in addressing the use of FRTs and FRT bias. However, the FTC possesses limited authority in this context and has historically struggled to compel compliance from large corporations. Thus, a new agency, specifically authorized to regulate and eliminate issues of bias that arise from commercial FRT applications, is needed to effectively address the presence and effect of bias within FRTs.

A. The States’ privacy protections for consumers, comprised of a patchwork of state and municipal regula tions, are inadequate to sufficiently address the issues of bias anticipated from the commercial use of FRTs.

In the absence of federal laws that regulate the commercial use of AI, much less FRTs, state and city laws have attempted to fill the regulatory gap. State governments may be regarded and valued as “living laboratories” in some respects, but their collective piecemeal legislation concerning commercial AI and FRT use may negatively impact the reduction of bias in FRTs and could likely lead to a deregulatory “race to the bottom.”

Significantly, three states–Illinois, Texas and Washington—have recognized the urgent need to address the burgeoning use of AI in the private sector and put privacy protections in place for consumers. The Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act, passed in 2008, requires commercial entities to obtain written consent in order to capture an individual’s biometric identifiers (including face geometry) or sell or disclose a person’s biometric identifier (740 Ill. Comp. Stat). The Illinois Act also places security and retention requirements on any collected biometric data (740 Ill. Comp. Stat). Although Texas and Washington have enacted similar laws, their laws vary significantly from Illinois’ in that only the attorney generals are authorized to enforce the laws against commercial entities (11 Tex. Bus. & Com. Code). Illinois’ law, on the other hand, includes a private right of action, which has led to several lawsuits against companies such as Clearview AI, Google, and Facebook (Greenberg, 2020; Yeung et al, 2020).

The variance among the entities empowered to enforce these states’ laws will likely create enforcement and compliance difficulties, particularly as it pertains to bias, because AI and FRTs inherently transcend state borders. Based on recent studies of the presence of bias in commercial FRTs, the selection of training data used to build algorithmic models appears to be the most important factor in reducing bias (Crumpler, 2020). Thus, the reduction of bias in commercial FRTs would be significantly hindered if companies are unsure whether they have access to certain images based on specific state laws. For example, Everalbum’s settlement with the FTC revealed that the international company compiled FRT training datasets by combining facial images it had extracted from Ever users’ photos with facial images obtained from publicly available datasets (Everalbum, Inc., n.d.). Everalbum’s FRT development was geographically constrained on a state-by-state basis to exclude images from users believed to be residents of Illinois, Texas, Washington, or the European Union (Everalbum, Inc., n.d.). From the perspective of increasing representative training datasets, the company’s exclusion of facial images from users in Texas and Illinois, specifically, would have negatively impacted the representation of Latinx people and other racial minorities (7) (Krogstad, 2020).

Given uncertainty among AI and FRT developers within the patchwork state regulatory scheme, paired with researchers’ recommendations to increase phenotypic and demographic representation in face datasets and algorithmic evaluations (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018), companies will likely want to conduct business in locations that enable them to have access to large amounts of data. In response, states may avoid enacting AI and FRT regulations that deter companies from conducting business in those states, resulting in what is termed as a deregulatory “race to the bottom” (Chen, 2022). If a “race to the bottom” situation was to occur in response to the patchwork of state AI regulations, then companies would likely seek to build and train FRTs in those states where consumers had less rights to their biometric data since the companies would have access to more information to compile larger datasets.

On the one hand, enabling companies’ ability to compile larger datasets seems like a great avenue to reduce bias in FRT applications, as the larger datasets would provide increased phenotypic and demographic diversity. However, a lack of state standards governing the quality and collection of biometric data could negatively impact FRT accuracy and, in turn, exacerbate the presence of biased results. According to one study, non-Caucasians may perform more poorly than Caucasians on FRTs, even with balanced training, because “faces of coloured skins are more difficult to extract and pre-process feature information, especially in dark situations” (Wang et al., 2019). Similarly, the “Gender Shade” researchers noted that default camera settings are often optimized to better expose lighter skin than darker skin (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018). This observation led the researchers to conclude that under-and overexposed images lose crucial information making them inaccurate measures of classification within artificial intelligence systems (Buolamwini & Gebru, 2018). If biased FRT performance is linked to the difficulty of extracting and pre-processing feature information from non-Caucasian faces, especially in dark situations; and, if sub-optimal camera lightening of non-Caucasian faces often produces images that lack crucial information rendering them inaccurate datapoints; then, lax state regulations on the quality and collection of biometric data will likely widen the discrepancy between FRTs’ performance on Caucasian and non-Caucasian faces, undermining efforts to reduce bias in commercial FRT use.

B. The current federal regulatory scheme lacks the scope and capacity to sufficiently address the issues of bias anticipated from the commercial use of FRTs.

The U.S. federal government, in passing the National AI Initiative Act of 2020 and creating the National AI Initiative Office (the “Office”), decided to primarily focus its resources on the support and growth of AI and its attendant technologies, including FRTs (Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, 2021). The Act also (1) expanded and made permanent the Select Committee on AI, which will serve as the senior interagency body responsible for overseeing the National AI Initiative; (2) codified the National AI Research Institutes and the National Sciences Foundation, collaborative institutes that will focus on a range of AI research and development areas, into law; (3) expanded AI technical standards to include an AI risk assessment framework; and (4) codified an annual AI budget rollup of Federal AI research and development investments (The White House Office of Science and Tech. Policy [OSTP], 2021). Further, on January 27, 2021, President Biden signed a memorandum titled, “Restoring trust in government through science and integrity and evidence-based policy making,” setting in motion a broad review of federal scientific integrity policies and directing agencies to bolster their efforts to support evidence-based decisions making (The White House Office of Science and Tech. Policy [OSTP], 2021). In spite of these nascent attempts to federally regulate commercial use of FRTs, the existing commercial applications of FRTs and the instances of bias that arise from such use remain largely unregulated.

The National AI Initiative Office lacks the capacity and authority to regulate bias arising from current commercial FRT use since, according to its enabling statute, the Office is principally concerned with supporting public and private AI innovation. The National AI Initiative Act describes the Office’s responsibilities as serving as a liaison between the government, industry, and academia; outreaching to the public, and promoting innovation (The White House, 2020).

None of the enumerated responsibilities described in the National AI Initiative Act authorize the Office to specifically regulate existing commercial AI use, let alone address any issues of bias. The first two responsibilities establish the Office’s authority to “provide technical and administrative support” to other federal AI Initiative committees and serve as a liaison on federal AI activities between a broadly defined group of public and private entities. The last two responsibilities charge the Office with reaching out to “diverse stakeholders” and promoting interagency access to the AI Initiative’s activities. The Office’s enabling statute does not clearly indicate whether the regulatory body has enforcement authority on private actors as there is no provision that confers on the Office the ability to promulgate rules or regulations. Likewise, the Office does not seem to have the power to impose sanctions in order to ensure industry compliance. Instead, the Office is focused on building coordination between the private sector and governmental entities to promote further AI innovation. Thus, the Office does not have explicit regulatory authority over any existing private use of AI or FRTs.

Supporters of the National AI Initiative Act and the Office may argue that the Office is appropriately situated to address issues of bias arising from the commercial use of FRTs, however that argument is undermined by the express statutory language of the Act. A supporter of the Office may point to the entity’s responsibility to serve as a liaison on federal AI activities between public and private entities to argue that, by facilitating the exchange of technical and programmatic information that could address bias in AI, the Office would help FRT developers reduce bias. However, the statute does not appear to enable the Office to influence or contribute to the substantive contents of the information shared between the public and private sectors about the AI Initiative activities. If the Office lacks the ability to influence the substance of information exchanged, then it also lacks the ability to specifically direct information sharing that could redress bias in commercial AI applications. A supporter of the Office may also point to its outreach responsibility to argue that the Office will work to address bias by reaching out to diverse stakeholders, including civil rights and disability rights organizations. Yet, the statutory language is vague as to the substance of this “regular public outreach” responsibility. Without a clearer indication that the Office’s public outreach efforts are directed toward or will somehow result in a reduction in AI and FRT bias, the assumption that coordinating public outreach with diverse stakeholders will sufficiently address bias in commercial FRT use remains unfounded. Hence, reducing bias that arises from the commercial use of FRTs is not an articulated central focus, nor an explicitly intended effect, of the Office’s enabling statute.

Close analysis of the statutory language establishing the National AI Initiative and the Office reveals that the Office will likely operate more like a governmental think-tank to ensure coordinated AI innovation than a regulatory body with enforcement power. Such a scheme is inadequate to properly address the existing issues of bias shown in today’s commercial FRTs since the AI Initiative will likely promulgate industry standards that stem from and reflect the market itself, including its apparent biases.

The few FTC regulatory decisions that have been handed down concerning existing commercial FRT applications are products of the FTC’s recent actions to regulate private AI use (Facebook, Inc., n.d.). Based on its latest posts and statements, the FTC anticipates broadening its regulation of private AI and FRT use to not only focus on user consent, but also biased algorithms (Jillson, 2021). However, the FTC has limited enforcement power to sufficiently address the wide-ranging applications of FRTs and reduce the perpetuation of bias.

The Federal Trade Commission Act empowers the FTC to, among other things:

(a) prevent unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce;

(b) seek monetary redress and other relief for conduct injurious to consumers; and

(c) prescribe rules defining with specificity acts or practices that are unfair or deceptive, and establishing requirements designed to prevent such acts or practices (15 U.S.C. §§ 41-58).

As stated in its enabling statute, the FTC’s enforcement power is limited to “unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce” (15 U.S.C. §§ 41-58) The FTC asserts its authority over certain issues or subject areas by deeming a certain commercial practice unfair or deceptive, which is exactly what the FTC did when it released its recent AI blog post categorizing the use or sell of “biased algorithms” as an unfair and deceptive practice. Yet, the FTC will likely run into future enforcement issues in trying to prevent the use and sale of biased algorithms because they lack the willingness to enforce orders and expertise in AI training and development. Despite the FTC’s recent blog post indicating its intention to bring enforcement actions related to biased algorithms, FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra provided a statement to the Senate noting that “Congress and the Commission must implement major changes when it comes to stopping repeat offenders” and that “since the Commission has shown it often lacks the will to enforce agency orders, Congress should allow victims and state attorneys general to seek injunctive relief in court to halt violations of FTC orders (Federal Trade Commission [FTC], 2021).

In support of his first suggestion concerning the issue of repeat offenders, Commissioner Chopra emphasized that, “[w]hile the FTC is quick to bring down the hammer on small businesses, companies like Google know that the FTC simply is not serious about holding them accountable” (Federal Trade Commission [FTC], 2021). If the FTC is currently struggling to “turn the page on [their] perceived powerlessness” (Federal Trade Commission [FTC], 2021), then it follows that it is most likely ill-suited to successfully take on emerging global leaders in commercial AI technology. Furthermore, the Commissioner’s plea for Congress to allow victims and state attorneys general to access the courts for injunctive relief underscores the FTC’s inability and unwillingness to enforce its orders. Shifting the burden onto consumers and judges to regulate the exploding commercial use of FRTs and reduce bias is less than ideal as the courts lack the expertise and resources to adequately address bias in commercial FRT use. Also, courts are bound by justiciability principles, which limits their ability to regulate and reduce bias. Therefore, Congress should create a new agency that is solely authorized to address issues of bias in commercial FRT use, has power to regulate, and teeth to go after private parties who violate its regulations.

C. Congress must establish a new federal agency specifically, but not solely, authorized to regulate and eliminate issues of bias that arise from commercial FRT applications.

In order to effectively address the pervasiveness of bias in private FRT use, Congress must establish a new regulatory agency specifically, but not solely, authorized to regulate and eliminate issues of bias that arise from commercial FRT applications. The new agency should be created according to the following enabling statute to ensure its appropriate scope and capacity:

The [agency] is empowered, among other things, to:

(a) prevent private entities’ development, use, or sale of FRTs in circumstances that perpetuate bias based on ethnic, racial, gender, and other human characteristics recognizable by computer systems;

(b) seek monetary redress or other relief for injuries resulting from the presence of bias in FRTs; (c) prescribe rules and regulations defining with specificity circumstances known or reasonably foreseeable to perpetuate bias that is prejudicial to established human and legal rights, and establishing standards designed to prevent such circumstances;

(d) gather and compile data and conduct investigations related to private entities’ development, testing, and application of FRTs; and

(e) make reports and legislative recommendations to Congress and the public. (8)

Part (a) of the new agency’s enabling statute delineates the scope of the agency’s enforcement power to specifically regulate private entities’ development, use or sale of FRTs in settings that perpetuate bias. The phrase “development, use, or sale” is designed to extend the agency’s regulatory scope to include the development or creation of FRTs in recognition of the fact that biases can originate from either the algorithm or the training dataset. Including the development stage within the agency’s regulatory authority will allow the agency to effectively regulate the sources of bias—the algorithm, training datasets, and photo quality. Additionally, the inclusion of all three stages—development, use, and sale—enable the agency to have the conceptual framework and authority to regulate any future sources of bias that are yet to be discovered (9) (Learned-Miller et al., 2020).

Part (b) confers the agency the power to impose sanctions in the form of monetary penalties or other appropriate type of relief for injuries caused by a private party’s violation of the agency’s regulations. Part (b) is of utmost importance since it will give the agency power to bring down the hammer on violating entities and shirk the perception of “powerlessness.” The agency will compel compliance from large companies by bringing timely actions against violating parties, requiring violating parties to make material changes to their algorithms that eliminate or significantly reduce bias, and maintaining a reputation for rigorously holding companies accountable for their algorithms.

Part (c) functions hand-in-hand with Part (b) in that the agency’s promulgation of rules and regulations creates the legal claims through which the agency can seek monetary redress or other forms of relief from violating companies. Requiring the agency to prescribe rules and regulations that specifically define circumstances known or reasonably foreseeable to perpetuate bias will require significant technical expertise. The agency should employ and regularly consult with preeminent AI and FRT scholars and researchers so that it can stay abreast of industry standards, norms, and developments. The agency must also develop rigorous testing standards to identify and address algorithms’ rates of bias, which will require it to compile large datasets that are phenotypically and demographically representative.

Part (d) significantly empowers the agency to continually request information from private FRT developers so that it can promulgate rules and standards that can effectively address the identified sources of bias in commercial FRT applications. Without the power to gather and compile data, the agency’s regulations and standards would run the risk of becoming obsolete or irrelevant to the FRT industry, which would hinder its ability to reduce bias. Similarly, the power to conduct investigations related to FRT development, testing, and applications is crucial to the agency’s regulatory authority so that the agency can actively ensure companies’ compliance without needing to wait on injured parties, who often lack AI expertise or access to representation, to bring claims. Based on its investigations, the agency can further ensure the sustained reduction in FRT bias by making reports and recommendations to Congress and the public.

Part (e) can be best realized by the agency because of its broad authority to regulate every aspect of FRT development and application. Thus, the agency sits at a critical juncture between FRT developers, legislators, and the public. Consequently, the agency can emphasize legislative reform as needed to effectively reduce bias and contribute to a nascent body of knowledge that the public has only begun to understand.

A new federal agency, empowered to investigate and regulate FRT development, testing, and application can reduce the presence of bias more effectively than the current regulatory scheme because of its broad authority and enforcement power. The FTC is limited in its authority to regulate bias, and its regulatory power has repeatedly bowed to the will of large corporations. Furthermore, it is not clear whether the Office has the authority to even promulgate rules or standards. Yet, FRT technology is a growing market, and researchers have only scratched the surface of how FRTs perpetuate bias. To this end, the Association of Computing Machinery’s U.S. Technology Policy Committee observed that industry and government have adopted FRTs “ahead of the development of principles and regulations to reliably assure their consistently appropriate and non-prejudicial use” (Association for Computing Machinery [ACM], 2020). A new agency, specifically targeting the development, training, and application of FRTs can have the necessary breadth and expertise to reduce existing sources of bias and discover unknown sources of bias. Furthermore, the agency’s narrowly tailored focus on FRTs can help to lay a foundation for its future expanded regulatory authority over additional AI attendant technologies, which are likely more complex systems. Since large corporations have not dealt with the new agency yet, the agency will be able to set itself apart from agencies with waning respect from corporations by strictly enforcing its regulations, erring on the side of caution, and crafting settlement agreements with provisions that require violators to make material changes to reduce FRT bias. Though the existence of completely unbiased FRTs is sure to be difficult to realize, the new agency will deploy all of its authority and resources to reducing FRT bias to the point of elimination.

Recommendations

The inundation of commercial facial recognition technology coupled with a lagging federal regulatory framework to govern commercial FRT development and use has led to a precarious environment where individuals bear the un- due burden of redressing unprecedented harms. The following policy recommendations, while ambitious, aim to support a national regulatory scheme that would reduce the frequency and severity of FRT bias and discrimination:

- Establish a federal agency with the explicit authority to regulate commercial AI and its attendant technolo- gies, like FRTs, in accordance with the following enabling statute:

The [agency] is empowered, among other things, to:

(a) prevent private entities’ development, use, or sale of FRTs in circumstances that perpetuate bias based on ethnic, racial, gender, and other human characteristics recognizable by computer systems;

(b) seek monetary redress or other relief for injuries resulting from the presence of bias in FRTs; (c) prescribe rules and regulations defining with specificity circumstances known or reasonably foreseeable to perpetuate bias that is prejudicial to established human and legal rights, and establishing standards designed to prevent such circumstances;

(d) gather and compile data and conduct investigations related to private entities’ development, testing, and application of FRTs; and

(e) make reports and legislative recommendations to Congress and the public.

- Create uniform guidelines for states’ regulation of the commercial collection and use of biometric data;

- Develop and encourage the increased implementation of phenotypically and demographically diverse face datasets in commercial FRT development, training, and evaluation.

Footnotes

- Khortlan Becton graduated summa cum laude from the University of Alabama with Bachelor of Arts degrees in Religious Studies and African American Studies, received a Master of Theological Studies from Vanderbilt Divinity School, and a Juris Doctor from Temple School of Law. Khortlan is a Truman Scholar Finalist, a member of Phi Beta Kap- pa, and recipient of numerous awards from the various academic institutions that she has attended.

While attending law school, Khortlan began studying and advocating for the regulation of artificial intelligence technologies, including facial recognition technology. She served as lead author for a summary of recent literature on algorithmic bias in decision-making and related legal implications. That paper’s co-author, Professor Erika Douglas (Temple School of Law), presented the literature review at the American Bar Association’s Antitrust Spring Meeting in 2022.Through holding various service and leadership roles, Becton has developed a deep appreciation for creative and collaborative problem-solving to address intergenerational issues of poverty and systemic inequality. Becton has continued to pursue her passion for education and justice by launching The Restorative Education Institute. The Institute is a non-profit organization purposed to equip youth and adults to practice anti-racism through historical education and substantive reflection. - The FTC, which is playing an active role in the misuse of facial recognition, previously imposed a $5 billion penalty and new privacy restrictions on Facebook in 2019. Similar to the allegations against Everalbum, the complaint against Facebook alleged that Facebook’s data policy was deceptive to users who have Facebook’s facial recognition setting because that setting was turned on by default, while the updated data policy suggested that users would need to opt-in to having facial recognition enabled.

- The four large datasets of photographs are: (1) Domestic mugshots collected in the U.S.; (2) Application photographs from a global population of applicants for Immigration benefits; (3) Visa photographs submitted in support of visa applicants; and (4) Border crossing photographs of travelers entering the U.S.

- This effect is generally large, with a factor of 100 more false positives between countries.

- These differing results relate to image quality: The mugshots were collected with a photographic setup specifically standardized to produce high-quality images across races; the border crossing images deviate from face image quality standards.

- The OMB memorandum defines “narrow” AI as “go[ing] beyond advanced conventional computing to learn and perform domain-specific or specialized tasks by extracting information from data sets, or other structured or unstructured sources of information.”

- According to Pew Research, Texas is one of two states with the most Latinx people at 11.5 million. Illinois’ Latinx population increased from 2010 to 2019 by 185,000 people.

- The new agency’s enabling statute is modeled after the Federal Trade Commission Act because the Act succinctly embodies the power of a narrowly focused agency. The FTC Act is primarily focused on “unfair and deceptive acts or practices affecting commerce,” which has contributed to the FTC’s broad authority. The new agency will need a similar breadth in their jurisdictional scope since researchers have only begun to scratch the surface of bias in FRT applications.

- Specifically defining the concepts used to describe the creation and management of FRTs is of utmost importance to delineating the scope of not only the AI attendant tech- nology, but also the breadth of an agency’s regulatory framework. Researchers have recently endeavored to provide specific definitions for the creation of a federal regulatory scheme for FRTs that will likely be a necessary addition to the enabling statutory language proposed here.

References

11 Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 503.001 (2019). 11 Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 503.001(D).

15 U.S.C. §§ 41-58.

740 Ill. Comp. Stat. 14/1 (2008).

740 Ill. Comp. Stat. 14/20 (2008).

Amazon Web Services [AWS]. (2021). The Facts on Facial Recognition with Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved from https://aws.amazon.com/rekognition/the-facts-on-facial-recognition-with-artificial-intelligence/

Association for Computing Machinery [ACM]. (2020, June 30). U.S. Technology Policy Committee: Statement on Principles and Prerequisites for the Development, Evaluation and Use of Unbiased Facial Recognition Technologies. Retrieved from https://www.acm.org/binaries/content/assets/public-policy/ustpc-facial- recognition-tech-statement.pdf

Brownlee, J. (2019, July 5). A gentle introduction to deep learning for face recognition. Machine Learning Mastery. Retrieved from https://machinelearningmastery.com/introduction-to-deep-learning-for-face-recognition/

Buolamwini, J., & Gebru, T. (2018). Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Proceedings of Machine Learning Research 81, 1-15.

Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.100 – 1798.199.100 (2018).

Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.150, § 1798.199.90 (2018).

Calvello, M. (2019, Oct 23). 22 eye-opening facial recognition statistics for 2020. Learn Hub. Retrieved from https://learn.g2.com/facial-recognition-statistics

Chellappa, R., Phillips, P.J., Rosenfeld, A., & Zhao, W. (2003). Face recognition: A literary survey. ACM Journals, 35(4). https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/954339.954342

Chen, J. (2022, Oct. 3). Race to the bottom. Investopedia. Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/ race-bottom.asp#:~:text=The%20race%20to%20the%20bottom%20refers%20to%20a%20competi- tive%20situation,can%20also%20occur%20among%20regions

Crumpler, W. (2020, May 1). The problem of bias in facial recognition. Center for Strategic and International Studies Blog Post. Retrieved from https://www.csis.org/blogs/technology-policy-blog/ problem-bias-facial-recognition

Everalbum, Inc., (n.d.) FTC Complaint No. 1923172. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/ cases/everalbum_complaint.pdf

Facebook, Inc., FTC Stipulated Order No. 19-cv-2184. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ documents/cases/182_3109_facebook_order_filed_7-24-19.pdf

Federal Trade Commission [FTC]. (2019, July 24). FTC imposes $5 billion penalty and sweeping new privacy restrictions on Facebook. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2019/07/ ftc-imposes-5-billion-penalty-sweeping-new-privacy-restrictions

Federal Trade Commission [FTC]. (2021, April 20). Prepared opening statement of Commissioner Rohit Chopra, U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation hearing on “Strengthening the FederalTrade Commission’s authority to protect consumers”. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/system/ files/documents/public_statements/1589172/ final_chopra_opening_statement_for_senate_commerce_committee_20210420.pdf

Federal Trade Commission [FTC]. (2021, Feb. 10). Protecting Consumer privacy in a time of crisis, remarks of acting Chairwoman Rebecca Kelly Slaughter, future of privacy forum. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/ system/files/documents/public_statements/1587283/fpf_opening_remarks_210_.pdf

Federal Trade Commission [FTC]. (2021, Jan. 8). Statement of Commissioner Rohit Chopra, in the matter of Everalbum and Paravision, Commission File No. 1923172. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/system/ files/documents/public_statements/1585858/ updated_final_chopra_statement_on_everalbum_for_circulation.pdf

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP. (2021, April 23). Artificial intelligence and automated systems legal update (1Q21). Retrieved from https://www.gibsondunn.com/ artificial-intelligence-and-automated-systems-legal-update-1q21/#_ftn3

Greenberg, P. (2020, Sept. 18). facial recognition gaining measured acceptance. State Legislatures Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.ncsl.org/research/telecommunications-and-information-technology/ facial-recognition-gaining-measured-acceptance-magazine2020.aspx

Grisales, C. (May 18, 2023). Schumer meets with bipartisan group of senators to build a coalition for AI law, NPR.org. https://www.npr.org/2023/05/18/1176894731/ schumer-meets-with-bipartisan-group-of-senators-to-build-a-coalition-for-ai-law

Grother, P., Ngan, M., & Hanaoka, K. (20190. Face Recognition Vendor Test (FRVT) Part 3: Demographic Effects. Natl. Inst. of Stand. & Technol., NISTIR 8280. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8280

The White House. (2020, Nov. 17). Guidance for regulation of artificial intelligence applications, H.R. 6395, § 5102. 2, OMB Op. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/ uploads/2020/11/M-21-06.pdf

Heater, B. (2020, Nov. 4). Portland, Maine passes referendum banning facial surveillance, Techcrunch.com. Retrieved from https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/04/ portland-maine-passes-referendum-banning-facial-surveillance/

Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP. (2020, Sept. 10). Portland, Oregon first to ban private-sector use of facial recognition technology. Privacy & Information Security Law Blog. Retrieved from https://www.huntonprivacyblog. com/2020/09/10/portland-oregon-becomes-first-jurisdiction-in-u-s-to-ban-the-commercial-use-of- facial-recognition-technology/

IBM. (2020, June 3). What is artificial intelligence (AI)? IBM Cloud Education. Retrieved from https://www.ibm. com/cloud/learn/what-is-artificial-intelligence

Jillson, E. (2021, April 19). Aiming for truth, fairness, and equity in your company’s use of AI. Federal Trade Commission [FTC]. Retrieved from https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/blogs/business-blog/2021/04/ aiming-truth-fairness-equity-your-companys-use-ai

Kang, C. OpenAI’s Sam Altman Urges A.I. Regulation in Senate Hearing, NYTimes.com, (May 16, 2023), https:// www.nytimes.com/2023/05/16/technology/openai-altman-artificial-intelligence-regulation.html

Krogstad, J.M. (2020, July 10). Hispanics have accounted for more than half of total U.S. population growth since 2010. Pew Research. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/07/10/ hispanics-have-accounted-for-more-than-half-of-total-u-s-population-growth-since-2010/#:~: text=Some%20of%20the%20nation’s%20largest,of%20the%20nation’s%20Hispanic%20population

Learned-Miller, E., Ordóñez, V., Morgenstern, J., & Buolamwini,J. (2020, May 29). Facial recognition technologies in the wild: A call for a federal office. Center for Integrative Research in Computing and Learning Sciences. Retrieved from https://people.cs.umass.edu/~elm/papers/FRTintheWild.pdf

MarketsandMarkets, (2020, Dec. 2). Facial recognition market worth $8.5 billion by 2025. Retrieved from https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/PressReleases/facial-recognition.asp

Metz, R. (2020, Sept. 9). Portland passes broadest facial recognition ban in the US. CNN.com, Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2020/09/09/tech/portland-facial-recognition-ban/index.html

Najibi, A. (2020, Oct. 4). Racial discrimination in face recognition technology. Harvard University, Science in the News. Retrieved from https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2020/ racial-discrimination-in-face-recognition-technology/#

National Artificial Intelligence Initiative Act. U.S. Public Law 116-283 (2020).

Natl. Inst. of Stand. & Technol. [NIST]. (2018, Nov. 30). NIST evaluation shows advance in face recognition software’s capabilities. Retrieved from https://www.nist.gov/news-events/news/2018/11/ nist-evaluation-shows-advance-face-recognition-softwares-capabilities

Sakin, N. (2021, Feb. 11). Will there be federal facial recognition in the U.S.? International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP). Retrieved from https://iapp.org/news/a/u-s-facial-recognition-roundup/

Samuel, S. (2019, March 6). A new study finds a potential risk with self-driving cars: Failure to detect dark-skinned pedestrians. Vox.com. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/3/5/18251924/ self-driving-car-racial-bias-study-autonomous-vehicle-dark-skin

Solender, A. & Gold, A. (April 13, 2023). Scoop: Schumer lays groundwork for Congress to regulate AI, Axios.com, https://www.axios.com/2023/04/13/congress-regulate-ai-tech/

Thales Group. (2021, March 30). Facial recognition: Top 7 trends (tech, vendors, markets, use cases & latest news). Retrieved from https://www.thalesgroup.com/en/markets/digital-identity-and-security/government/ biometrics/facial-recognition

The White House Office of Science and Tech. Policy [OSTP]. (2021, Jan. 12). The White House launches the National Artificial Intelligence Initiative Office. Retrieved from https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/ briefings-statements/white-house-launches-national-artificial-intelligence-initiative-office/

The White House Office of Science and Tech. Policy [OSTP]. (2022a). Blueprint for an AI bill of rights. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/ai-bill-of-rights/

The White House Office of Science and Tech. Policy [OSTP]. (2022b). Biden-Harris administration announces key actions to advance tech accountability and protect the rights of the American public. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2022/10/04/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration- announces-key-actions-to-advance-tech-accountability-and-protect-the-rights-of-the-american-public/

Towards Data Science. (Sept. 14, 2018). Clearing the confusion: AI vs machine learning vs deep learning differences. Retrieved from https://towardsdatascience.com/clearing-the-confusion-ai-vs-machine-learning- vs-deep-learning-differences-fce69b21d5eb

Wang, M., Deng, W., Hu, J., Xunqiang, T., & Huang, Y. (2019). Racial faces in-the-wild: Reducing bias by information maximization adaption network, IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Korea (South). pp. 692-702, doi: 10.1109/ICCV.2019.00078 https://arxiv.org/pdf/1812.00194.pdf

Wash. Rev. Code § 19.375.020 (2017).

Wash. Rev. Code §19.375.030 (2017).

Yeung, D., Balebako, R., Gutierrez, C.I., & Chaykowsky, M. (2020). Face recognition technologies: Designing systems that protect privacy and prevent bias. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

Zakrzewski, C., Tiku, N., Lima C. & Oremus W. (May 16, 2023). OpenAI CEO tells Senate that he fears AI’s potential to manipulate views, Washington Post.com, https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/05/16/ ai-congressional-hearing-chatgpt-sam-altman/

To say the world is in the throes of a technological revolution spearheaded by artificial intelligence (“AI”), and automation, may be one of the most understated observations of this century. While “Fake News” ran rampant on social and other media and influenced the November 2016 presidential election, that election provided ample warning of how media manipulated to mislead can have enormous negative consequences for every segment of life, including personal and employment relationships, national security, elections, media, etc.

To say the world is in the throes of a technological revolution spearheaded by artificial intelligence (“AI”), and automation, may be one of the most understated observations of this century. While “Fake News” ran rampant on social and other media and influenced the November 2016 presidential election, that election provided ample warning of how media manipulated to mislead can have enormous negative consequences for every segment of life, including personal and employment relationships, national security, elections, media, etc. It is ironic, if not exhausting, that seemingly basic issues, like the right to vote, remain at the forefront of dissension in American life. However, as Coretta Scott King poignantly stated, the struggle for civil rights “is a never-ending process. Freedom is never really won. You earn it and win it in every generation.” When speaking about civil rights, the late Dr. Benjamin L. Hooks would say to young people, “it’s your time now.” The Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change programming seeks to fulfill the mandate of the civil rights movement and its legacies.

It is ironic, if not exhausting, that seemingly basic issues, like the right to vote, remain at the forefront of dissension in American life. However, as Coretta Scott King poignantly stated, the struggle for civil rights “is a never-ending process. Freedom is never really won. You earn it and win it in every generation.” When speaking about civil rights, the late Dr. Benjamin L. Hooks would say to young people, “it’s your time now.” The Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change programming seeks to fulfill the mandate of the civil rights movement and its legacies. Over the last two weeks, many people, both black and white, have contacted me expressing their outrage over the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020 by the police asking “What can I do? Where do we start to fix this problem?” They, like me, know that police brutality and racism are not just a Black people’s problem; it’s an American problem, which makes it a white people’s problem too.

Over the last two weeks, many people, both black and white, have contacted me expressing their outrage over the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020 by the police asking “What can I do? Where do we start to fix this problem?” They, like me, know that police brutality and racism are not just a Black people’s problem; it’s an American problem, which makes it a white people’s problem too. The horrific murder of George Floyd is a call to action by each of us to end police brutality and racism. Only in this way, can African Americans and other brown people enjoy life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness – a promised made to each us in the Declaration of Independence and by the U.S. Constitution. We the People have work to do. Please get started. Now.

The horrific murder of George Floyd is a call to action by each of us to end police brutality and racism. Only in this way, can African Americans and other brown people enjoy life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness – a promised made to each us in the Declaration of Independence and by the U.S. Constitution. We the People have work to do. Please get started. Now. This year’s winner stood out among this outstanding group. The winner of the 2017 Hooks Institute National Book Award, Locking Up Our Own by James Forman, Jr.’s, is a tremendous contribution to today’s vibrant discussions about mass incarceration and the criminal justice systems that continue to devastate black communities. It provides a layer of complexity to those discussions by investigating local decisions that gave rise to mass incarceration, decisions that were often endorsed by black leaders. With a compelling personal touch, Forman frames the problem as a series of smaller decisions rather than as a massive conspiracy, providing a sense of hope that there is an opportunity to incrementally confront an incrementally-constructed system. This book is a worthy winner of the Hooks Institute’s National Book Award as it illuminates readers on a central civil rights struggle of our time.

This year’s winner stood out among this outstanding group. The winner of the 2017 Hooks Institute National Book Award, Locking Up Our Own by James Forman, Jr.’s, is a tremendous contribution to today’s vibrant discussions about mass incarceration and the criminal justice systems that continue to devastate black communities. It provides a layer of complexity to those discussions by investigating local decisions that gave rise to mass incarceration, decisions that were often endorsed by black leaders. With a compelling personal touch, Forman frames the problem as a series of smaller decisions rather than as a massive conspiracy, providing a sense of hope that there is an opportunity to incrementally confront an incrementally-constructed system. This book is a worthy winner of the Hooks Institute’s National Book Award as it illuminates readers on a central civil rights struggle of our time.

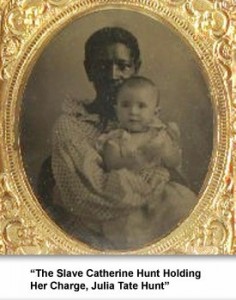

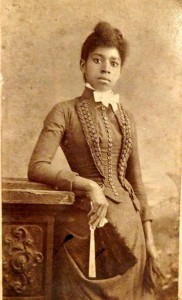

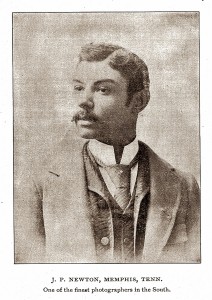

Race, Representation, and Photography in 19th Century Memphis: from Slavery to Jim Crow, is an in-depth study of African American visual culture and history. Using Victorian era photographs, pictorial illustrations, and engravings from local and national archives, I examine intersections of race and image within the context of early African American community building. The city of Memphis serves as the case study, wherein black agency and photographic images intersect to reveal the hidden history of racialized experiences in the urban south during slavery and freedom following the Civil War. My interdisciplinary research links the social history of photography with the fields of art history, visual culture, critical race studies, gender, and southern studies.

Race, Representation, and Photography in 19th Century Memphis: from Slavery to Jim Crow, is an in-depth study of African American visual culture and history. Using Victorian era photographs, pictorial illustrations, and engravings from local and national archives, I examine intersections of race and image within the context of early African American community building. The city of Memphis serves as the case study, wherein black agency and photographic images intersect to reveal the hidden history of racialized experiences in the urban south during slavery and freedom following the Civil War. My interdisciplinary research links the social history of photography with the fields of art history, visual culture, critical race studies, gender, and southern studies.