By Rebekkah Yisrael Mulholland

PhD Candidate, History Department. University of Memphis

Recently, while going through some stuff in my closet, I came across a note a friend wrote for me back in 2010 as we wrapped up our study abroad trip in South Africa. She wrote many humbling and beautiful things in this note. One of the things that stood out to me was her referring to me as a strong (black) woman. As I read that line, I wondered what led to her defining me in such a way. I read that note, particularly that line, repeatedly. As I did so, I thought back to where I was mentally. The year 2010 started out on a strong note. I was accepted into graduate school to obtain a Master’s in Humanities with a concentration in African and African American Studies. In February of that year, I decided to study abroad in South Africa. In June, we began preparing for our July departure. One Friday night in June, I almost passed out in the shower, which caused to me freak out. I thought I was dying. My head was spinning, my heart racing, and my body became too heavy to hold up.

The following Monday morning, I went to Student Health Services on campus to see what was up. I had very low blood counts. As it turned out, I was severely anemic. This not knowing what was going on with my body, led to the next two and a half years of anxiety and panic attacks. During this time, I had daily anxiety and/or panic attacks. I found myself staying in my apartment out of fear that I would have an attack in public. I limited my outside travels to going to class, work, and occasional outings with friends. If it had not been for school, I may have suffered a lot more than I did. Graduate school was a great experience for me. On the outside, I was cool as a cucumber, on the inside, I was suffering. At home, I was suffering by myself and in silence. I remember telling my mother a little bit of the things I was going through. Late one night, I called her because I was having shooting pains in my right arm. I knew it was not a heart attack, but the pain was enough to scare me. Therefore, she drove from her home in Cincinnati to Dayton where I was living and attending school to take me to the ER. While waiting to be seen, my mother handed me an article and said to me, “Here read this. This sounds like you.” The first line of the article read, “I feel like I am dying.” This did sound like me. At the time, I felt and even said this line at least twice a day. The article was about Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). I was suffering from GAD. Really, just from almost passing out in my shower late one night about roughly four months before reading this article? This experience goes against the image and definition of the strong black woman or does it?

The following Monday morning, I went to Student Health Services on campus to see what was up. I had very low blood counts. As it turned out, I was severely anemic. This not knowing what was going on with my body, led to the next two and a half years of anxiety and panic attacks. During this time, I had daily anxiety and/or panic attacks. I found myself staying in my apartment out of fear that I would have an attack in public. I limited my outside travels to going to class, work, and occasional outings with friends. If it had not been for school, I may have suffered a lot more than I did. Graduate school was a great experience for me. On the outside, I was cool as a cucumber, on the inside, I was suffering. At home, I was suffering by myself and in silence. I remember telling my mother a little bit of the things I was going through. Late one night, I called her because I was having shooting pains in my right arm. I knew it was not a heart attack, but the pain was enough to scare me. Therefore, she drove from her home in Cincinnati to Dayton where I was living and attending school to take me to the ER. While waiting to be seen, my mother handed me an article and said to me, “Here read this. This sounds like you.” The first line of the article read, “I feel like I am dying.” This did sound like me. At the time, I felt and even said this line at least twice a day. The article was about Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). I was suffering from GAD. Really, just from almost passing out in my shower late one night about roughly four months before reading this article? This experience goes against the image and definition of the strong black woman or does it?

In a BuzzFeed article, “It’s Time to Say Goodbye to TV’s Strong Black Woman” by Nichole Perkins, this archetype is defined as a woman “who can take on the world with no thought of their own needs, without emotion, and without complaint.” This image of black womanhood puzzles me. While this superhero image of black womanhood is supposed to be a compliment, why do we have to suppress our emotions, neglect our needs, and suck up how we feel in order to not appear weak? In order to be what we need to be for others, how does neglecting ourselves help? This archetype is supposed to re-imagine and re-define black womanhood in the place of the negative stereotypes that have been the perceptions of black womanhood. While this model of black womanhood is supposed to be a compliment, it is dangerous as it causes black women to suffer in silence as we are thought to be superwomen.

What I mean by this archetype being dangerous for black women are the psychological affects it has on us. Within the black community, mental health is not a topic that is discussed, and therapy is not an option for many for various reasons. Within the community, mental health tends to be stigmatized and most would say that going to church would solve all problems. Among black women, depression is one of those unspoken dangers. When it comes to the mental health of adolescent girls, no one talks about the black girls who suffer from eating disorders, cutting, and depression. Being a historian, I do trace these behaviors back to slavery when our many great grandmothers were supposed to suppress their feelings. They were physically and mentally brutalized and forced to keep such incidents to themselves and keep moving along. While the times may have changed, people’s attitudes about how we are to handle our mental (in)stabilities are often handled the same way, “keep it to yourself,” “don’t tell nobody,” “just don’t think about it,” and “you’re too strong to let that get you down.” These sayings are dangerous and detrimental to our health. We should not and do not have to suffer in silence.

What I mean by this archetype being dangerous for black women are the psychological affects it has on us. Within the black community, mental health is not a topic that is discussed, and therapy is not an option for many for various reasons. Within the community, mental health tends to be stigmatized and most would say that going to church would solve all problems. Among black women, depression is one of those unspoken dangers. When it comes to the mental health of adolescent girls, no one talks about the black girls who suffer from eating disorders, cutting, and depression. Being a historian, I do trace these behaviors back to slavery when our many great grandmothers were supposed to suppress their feelings. They were physically and mentally brutalized and forced to keep such incidents to themselves and keep moving along. While the times may have changed, people’s attitudes about how we are to handle our mental (in)stabilities are often handled the same way, “keep it to yourself,” “don’t tell nobody,” “just don’t think about it,” and “you’re too strong to let that get you down.” These sayings are dangerous and detrimental to our health. We should not and do not have to suffer in silence.

One of the most important things black women can do for themselves is learn self-care techniques. For me, the most important is therapy. The importance of having someone to talk to without a sermon or judgment cannot be stressed enough. It is my hope that as students make the decision to attend the University of Memphis that they are made aware of the Counseling Center and the Relaxation Zone on campus. Taking on the responsibility of balancing adulthood, coursework, and social lives makes a healthy mental state crucial to overall health and academic success. The center is a place for everyone. It is a safe space.

Please check out the Counseling Center’s website and find the resources offered: https://www.memphis.edu/counseling/

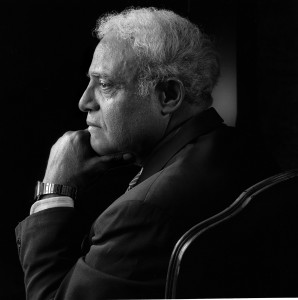

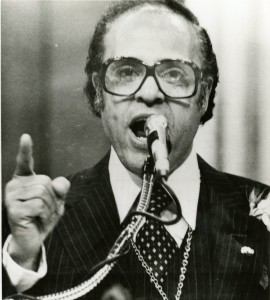

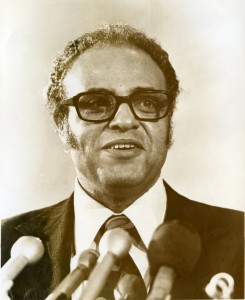

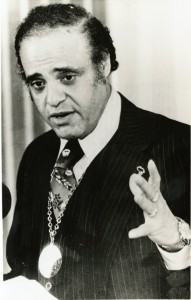

Rebekkah Mulholland is a Doctoral Candidate, currently pursuing a PhD in History at the U of M. Her interests are 19th and 20th century African-American history with an emphasis on black transgender women and gender nonconforming women of color within the Civil Rights, Black Power, and Trans Liberation Movements as well as in the era of mass incarceration. Rebekkah was the president of the Graduate Association for African-American History (GAAAH) at the UofM. She is assisting the Hooks Institute on several projects such as the Benjamin Hooks Papers Digitization Project and the 2019 National Book Award.

Rebekkah Mulholland is a Doctoral Candidate, currently pursuing a PhD in History at the U of M. Her interests are 19th and 20th century African-American history with an emphasis on black transgender women and gender nonconforming women of color within the Civil Rights, Black Power, and Trans Liberation Movements as well as in the era of mass incarceration. Rebekkah was the president of the Graduate Association for African-American History (GAAAH) at the UofM. She is assisting the Hooks Institute on several projects such as the Benjamin Hooks Papers Digitization Project and the 2019 National Book Award.

The Hooks Institute’s blog is intended to create a space for discussions on contemporary and historical civil rights issues. The opinions expressed by Hooks Institute contributors are the opinions of the contributors themselves, and they do not necessarily reflect the position of the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change or The University of Memphis.