On April 19, 2021, I had the opportunity to address the Canadian Forces College National Security Program. They were “virtually” touring cities in the American South to learn more about the particular needs of the population in each city. I was on the panel with Dr. Katherine Lambert-Pennington and Hooks Academic Research Fellow, Dr. Courtnee Mellon-Fant. Below is part of my presentation that addressed the role of faith in the movement for Black lives.

On April 19, 2021, I had the opportunity to address the Canadian Forces College National Security Program. They were “virtually” touring cities in the American South to learn more about the particular needs of the population in each city. I was on the panel with Dr. Katherine Lambert-Pennington and Hooks Academic Research Fellow, Dr. Courtnee Mellon-Fant. Below is part of my presentation that addressed the role of faith in the movement for Black lives.

In her important work chronicling the role of faith in the early days of the Ferguson resistance, Leah Gunning Francis argued that many of the BLM activists and protesters in the streets of Ferguson “demonstrated a very particular kind of embodiment of scripture and faith” and that activists “sought meaning through scripture in connection with their work for justice.”

Francis’ book is important because not only does the book chronicle the early days of the Ferguson resistance and the activism of BLM, but the book also chronicles the role of faith in those early days as well. It is important because the role of faith in BLM has always been one of contention. For instance, unlike the Civil Rights movement that it is often compared to, people often do not associate BLM as a faith-inspired movement or one that has anything to do with spirituality. This interpretation of the movement comes from a discourse that suggests perceived silence from churches—especially Black churches, during the early days of the movement.

However, despite the misgivings above on the role of faith and BLM, this did not stop many people of faith from joining the movement. In our research for our book, The Struggle Over Black Lives Matter and All Lives Matter, Amanda Nell Edgar and I in chapter 3, focused on our participant’s use of religious language and their own understandings of religion, faith, and spirituality that described their involvement with BLM. In short, we examine the “rhetoric of these narratives and examine how participants say that their faith, religion, or spirituality led them to support #BlackLivesMatter both online and “out in the streets.” What we discovered was that for many Black participants, the movement motivated a return to get more involved with their faith as well as an appreciation for the legacy of the Black Church.

BLM, Pentecostal Piety and the Role of Faith

But, how did people of faith reconcile the history of BLM and their own religious beliefs? One way that religion and communication scholar Christopher A. House suggest is that “many BLM activists self-identify as “spiritual but not religious” and their activism is animated by a deep spirituality that is personal, yet not connected traditionally to a religious institution. One of the BLM founders, Patrice Cullors remarked in an interview:

When you are working with people who have been directly impacted by state violence and heavy policing in our communities, it is really important that there is a connection to the spirit world. For me, seeking spirituality had a lot to do with trying to seek understanding about my conditions—how these conditions shape me in my everyday life and how do I understand them as part of a larger fight, a fight for my life. People’s resilience, I think, is tied to their will to live, our will to survive, which is deeply spiritual. The fight to save your life is a spiritual fight.

Elise Edwards suggests that while people who are engaging spirit “know that social transformation involves politics and policy,” they also believe that “transformative work is ultimately a spiritual effort that requires a shift in consciousness.” She also notes that this transformation is “dependent on inner change, the type of reorientation that religionists call conversion.” While this “spiritual transformation does not necessarily require the aid of formalized religious communities, African American communities have consistently drawn on Black religion to propel and sustain transformative justice movements and cultivate resistance to racism and other death-dealing forces.”

Our findings show the importance of spirit as well. As we ask participants how does your faith, or the role of spirit play in their support of BLM, many of them not only saw a connection but for some, it was a major reason for being part of the movement. In listening to their answers to our questions of faith and religion, much of it sounded like Andrew Wilkes’ notion of “Pentecostal Piety.”

For him, he sees this type of spirituality as crossing denominational, religious, faith, and moral lines because it has before. He writes

Although the civil rights movement is commonly linked with the Baptist denomination of Christianity, we don’t do it justice to remember it as denominational simply because it was so strongly associated with a certain, charismatic Christian clergyman of color. The ideas animating the movement were of far more diverse origin. The civil rights movement saw Black folks (and non-Black folks) consecrate the American dream by way of the prophetic Baptist theology of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, yes. But it also involved the anointed agnosticism of Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s founding executive director and the generative force of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Ella Baker. The radical Quaker vision of a Bayard Rustin next to the ethical humanism of an Asa Phillip Randolph were also blended in. And also in the mix was the subtle, yet significant tradition of faith-filled lay activists like Fannie Lou Hamer and Marian Wright Edelman.

Drawing from Wilkes, we note two major points about Pentecostal piety. First, Pentecostal piety places a heavy emphasis on the role of the spirit, and second, Pentecostal piety places a priority on prophetic action. Wilkes calls it a “subversive civil religion.” If this is true, then it is a civil religion that functions as a prophetic witness.

Many of our respondents would agree that BLM acts as a prophetic movement that provides a prophetic witness to the contextual realities faced by many African Americans. If this is true, then BLM is part of the long African American prophetic tradition. This tradition was

Birth from slavery and shaped in Jim and Jane Crow America, the African American version of the prophetic tradition has been the primary vehicle that has comforted and given voice to many African Americans. Through struggle and sacrifice, this tradition has expressed Black people’s call for unity and cooperation, as well as the community’s anger and frustrations. It has been both hopeful and pessimistic. It has celebrated the beauty and myth of American exceptionalism and its special place in the world, while at the same time damning it to hell for not living up to the promises and ideals America espouses. It is a tradition that celebrates both the Creator or the Divine’s hand in history—offering “hallelujahs” for deliverance from slavery and Jim and Jane Crow, while at the same time asking, “Where in the hell is God?” during tough and trying times. It is a tradition that develops a theological outlook quite different at times from orthodoxy—one that finds God very close, but so far away.

BLM is then just the latest in the history of people standing up and providing clarity and witness to the atrocities happening to Black bodies.

Conclusion

Though many believed that Black Churches were not as active as they once were, many understood the tradition and the legacy of the Civil Rights movement and saw themselves as connected to the tradition. The tradition also gave participants theological license to rethink, reshape, and reimagine what spirituality would look like in the BLM movement. This too, as we attempted to show, is part of the Black religious tradition. Birth in the resistance of a narrative that told Black people that they were not created in the image of God, Black people always had to put forth narratives that not only included them but also remind them that they too mattered.

For participants of faith, BLM offered a way of understanding a personal relationship with spirituality as a bridge to past civil rights leaders. In this way, larger movement history worked to draw in new social justice participants implicitly through their individual connections to the Spirit. BLM is not an explicitly religious organization. Yet the history of Black liberation organizes bubbles beneath the movement for Black lives. When activists engage in a spirituality that moves from moral suasion to bearing witness, they are discovering new and transformative ways to handle issues, problems, and concerns that Black people face daily. As a liberative and prophetic movement, BLM activists have drawn of the Black liberationists movements of the past and discerned the contextual realities confronting them today. In so doing, just like the civil rights activists that went before them, BLM is no different in that regard.

Andre E. Johnson is the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute Scholar in Residence and Associate Professor of Communication at the University of Memphis.

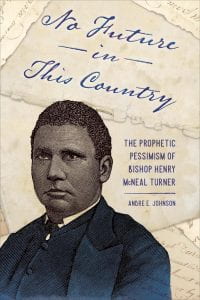

The Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change hosted the Inaugural Hooks Social Justice Series event where Hooks Scholar in Residence Andre E. Johnson gave a lecture on his book, No Future in This Country: The Prophetic Pessimism of Bishop Henry McNeal Turner. The event was moderated by UofM Communication and Film graduate student Tom Fuerst and took place February 24 at 1pm CST on the Hooks Institute’s Facebook Page and was free and open to the public.

The Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change hosted the Inaugural Hooks Social Justice Series event where Hooks Scholar in Residence Andre E. Johnson gave a lecture on his book, No Future in This Country: The Prophetic Pessimism of Bishop Henry McNeal Turner. The event was moderated by UofM Communication and Film graduate student Tom Fuerst and took place February 24 at 1pm CST on the Hooks Institute’s Facebook Page and was free and open to the public.