*Adapted from The Most Dangerous Negro in America”: Rhetoric, Race and the Prophetic Pessimism of Martin Luther King Jr. by Andre E. Johnson and Anthony J. Stone Jr.

*Adapted from The Most Dangerous Negro in America”: Rhetoric, Race and the Prophetic Pessimism of Martin Luther King Jr. by Andre E. Johnson and Anthony J. Stone Jr.

On April 4, 1968, on a balcony at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee in front of room 306, an assassin shot and killed the nation’s prophet of non-violence. The previous night, King delivered his infamous I’ve Been to the Mountain Top speech. In the speech, he called his audience to stand firm under the oppressive tactics of the Henry Loeb administration. He also called for them to turn up the pressure in their non-violence resistance. This meant massive economic boycotts.

We don’t have to argue with anybody. We don’t have to curse and go around acting bad with our words. We don’t need any bricks and bottles. We don’t need any Molotov cocktails. We just need to go around to these stores, and to these massive industries in our country, and say, “God sent us by here, to say to you that you’re not treating his children right. And we’ve come by here to ask you to make the first item on your agenda fair treatment, where God’s children are concerned. Now, if you are not prepared to do that, we do have an agenda that we must follow. And our agenda calls for withdrawing economic support from you.

But on the next day, King lay dead on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. Earlier that day he had worked on his sermon for Sunday, April 7. Though he lay dead, his associates found in his pocket the sermon notes he would have preached that Sunday if he had lived. The sermon title: “Why America May Go to Hell.”

Preaching economic boycotts and reflecting on why America may go to hell, may surprise admirers of King. While King today is largely considered one of the greatest Americans to ever

live, during his lifetime—and especially near the end of his life—King was one of the

most hated men in America. In a 1966 Gallop Poll, almost two-thirds of Americans had

an unfavorable opinion of King and the FBI named King “the most dangerous Negro in

America.

One reason for King’s declining popularity was his rhetoric on race. When examining King’s rhetoric, especially during the last year of his life, one would note that several of his speeches highlighted King’s growing understanding of race and racism. During the last year of his life, King’s confidence in American institutions or the American people living up to the ideas and ideals set forth in its sacred documents began to wane.

For instance, in his The Other America speech delivered at Stanford University on April 14, 1967, King called on his audience to see that the movement was heading towards another stage. King grounded this newfound insight on an understanding of racism that had eluded him in the past. He proclaimed, “Now the other thing that we’ve gotta come to see now that many of us didn’t see too well during the last ten years — that is that racism is still alive in American society and much more widespread than we realized. And we must see racism for what it is… It is still deeply rooted in the North, and it’s still deeply rooted in the South.” He closed this part of the speech by lamenting that

What it is necessary to see is that there has never been a single solid monistic determined commitment on the part of the vast majority of white Americans on the whole question of Civil Rights and on the whole question of racial equality. This is something that truth impels all men of goodwill to admit.

King’s position on race and racism would become even more pronounced in his speech America’s Chief Moral Dilemma, delivered May 10, 1967, to the Hungry Club. He starts by stating that “racism is still alive all over America. Racial injustice is still the Negro’s burden and America’s shame. And we must face the hard fact that many Americans would like to have a nation which is a democracy for white Americans, but simultaneously a dictatorship for Black Americans. We must face the fact that we have much to do in the area of race relations.”

King continued to address race and racism in his August 31, 1967 speech, the Three Evils of Society. In the speech, King revisited his arguments of racism and the prevailing white backlash. He argued that the “white backlash of today is rooted in the same problem that has characterized America ever since the Black man landed in chains on the shores of this nation.” While not implying that “all white Americans are racist,” he did critique the dominant idea that “racism is just an occasional departure from the norm on the part of a few bigoted extremists.” For King, racism may well be the “corrosive evil that will bring down the curtain on Western civilization” and warned that if “America does not respond creatively to the challenge to banish racism, some future historian will have to say, that a great civilization died because it lacked the soul and commitment to make justice a reality for all men.”

Leading up to the end of his life, King argued that what held America from becoming great was its racism. He further maintained that the movement had to face a resistance grounded in the nation’s racist heritage. Led by conservatives all across the country, the white backlash led King to realize that even with the earlier victories, a majority of white people still were not on board. He began to understand at a deeper level that the principles of the country he lauded and lifted in the past were mythic constructions. Therefore, he called for a moral revolution—challenging the nation’s long-held beliefs of freedom, democracy, justice, capitalism, and fairness.

King determined that the nation was sick and wondered aloud if things could get better. In his last sermon, Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution, delivered on March 31, 1968, at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC., King told the congregation that it is an “unhappy truth that racism is a way of life for the vast majority of white Americans, spoken and unspoken, acknowledged and denied, subtle and sometimes not so subtle—the disease of racism permeates and poisons a whole body politic.” For King, he realized that it was racism grounded in racist ideas and policies that hindered America from achieving its greatness.

While we do well to celebrate and commemorate the life and legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., let us remember his challenge to us today. Let us remember that right before his death in Memphis, Martin Luther King Jr. attempted to dismantle racism; believing that America may just go to hell on

his way to becoming one of the most hated men in America.

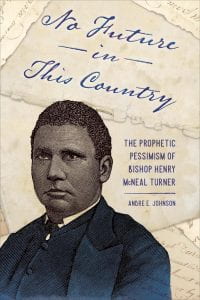

Andre E. Johnson is the Scholar in Residence at the Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change and Associate Professor of Rhetoric and Media Studies at the University of Memphis.