The University of Memphis team is now 2 weeks into our 2017 field season. Team members are: Suzanne Onstine, PhD, Director and Associate Professor at the University of Memphis

Archaeology/Egyptology students at the University of Memphis: Elizabeth Warkentin, Virginia Reckard, and Dustin Peasley

Physical Anthropology: Miguel Sanchez, MD, Jesus Herrerin, PhD, Rosa Dinares, PhD, Amr Shahat (PhD student, UCLA) and Casey Kirkpatrick (PhD student, Western Ontairo University).

We have just completed the analysis and x-ray of human remains excavated up to now. Each year we are more impressed with the preservation conditions of these remains; while they are broken and incomplete bodies, there is still a great deal of soft tissue preserved (heart, brain, and lung tissue, for example), and the information that can be gleaned from the broken bodies will help us write a better history of the people of Thebes in the 1st Milennium BCE. We are preparing articles about some of the more unusual cases examined this year.

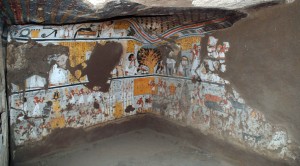

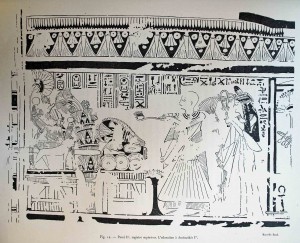

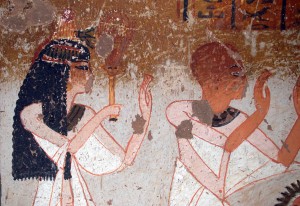

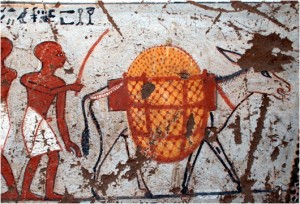

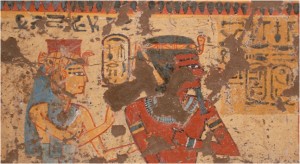

We will continue with clearance of the tomb next week until about February 15. We hope to find the original burial shaft of the 19th dynasty tomb owners, Panehsy and Tarenu, but with archaeology you never know what is just centimeters below the top layer dirt.

The West bank inspectorate in Qurnah