We here at the Memphis Massacre 1866 blog are collecting reflections from the movie Free State of Jones. If you would like to share your reflection on the movie, please email Andre E. Johnson at ajohnsn6@memphis.edu

We here at the Memphis Massacre 1866 blog are collecting reflections from the movie Free State of Jones. If you would like to share your reflection on the movie, please email Andre E. Johnson at ajohnsn6@memphis.edu

by Michael J. Steudeman

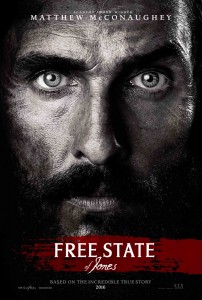

The Free State of Jones is really two movies. The first is a tightly-told story of a rebellion-within-a-rebellion led by Newton Knight during the Civil War. This movie has a familiar story arc, tracing one man’s journey from war defector to the leader of a de facto sovereign territory in Mississippi. Spanning only three years, this story happens in an easily-imagined geographic space, including Ellisville and its surrounding farms, plantations, and swamp.

The second movie is a punctuated set of vignettes, loosely structured around Knight’s life during Reconstruction. While the first movie covers three years of history, the second covers twelve in less than half the cinematic time. The sense of location is lost, as characters are uprooted and relocated. Events happen months, even years, apart, clarified with lengthy subtitles. The nearly 60 percent of reviewers on Rotten Tomatoes who have panned the movie concur that its effort to capture Reconstruction loses a sense of narrative coherence. It feels like a historian’s top-ten list of what “everyone should know about Reconstruction.” The Union Leagues, the Freedmen’s Bureau schools, the 15th Amendment, the immediate disfranchisement of black voters, the violence and intimidation of the Klan—each of these gets its moment. But only a moment. Once The Free State of Jones moves past 1865, reviewers complain, it becomes didactic, a series of incidents rather than a story.

These discrepancies reflect the chasm that divides Americans’ understanding of the Civil War from the tumultuous twelve years that followed. The first history is taught in middle and high school, and it sticks, as the binary narratives of war often do. To mark transitions during the Civil War narrative, the film follows the Ken Burns technique of pan-and-scanning over historical images of battlefields and Lincoln—as if to cue the viewer’s recollection, to say, “Remember? You learned this in school.” This device largely stops during the second half of the movie, likely in part because the most devastating moments of Reconstruction happened in the dark of night and were not caught by Matthew Brady’s camera.

The Reconstruction segments cannot rely on the images in many viewers’ heads, either, because they simply aren’t there. Little time is spent on these stories in school, let alone in popular culture. When Reconstruction is taught, it still remains insidiously inflected by the false narratives of the Southern “Lost Cause.” The narrative flaws that haunt The Free State of Jones are the very things that make the era difficult to teach. The period was a drawn-out series of often-anticlimactic power struggles, not a series of consequential battles. The Freedpeople and Unionists were displaced, through a protracted campaign of intimidation and murder. The politics were complicated. The hopes brought by the Union victory were slowly smothered over many years, not in a day. How does one capture all of this in a movie—or in just half of a movie—without moving so rapidly that the story is lost?

I suspect Gary Ross struggled with these problems during the decade he spent crafting the screenplay for The Free State of Jones. From its earliest announcement, through the trailers, and into its online descriptions, every indicator suggested that Free State of Jones would be a Civil War movie. The allure of the story for Ross, and undoubtedly to the film’s financiers, was Newton Knight’s saga during the war. Reading Ross’s commentary on the movie, though, it’s clear that he gradually discovered that the broad sweep of Reconstruction was just as important to capture. Like the historians he consulted, he kept encountering potent anecdotes of resilience and injustice, of black empowerment, of hopes inflamed and extinguished. This, he rightly recognized, is a story everyone should know.

Like so many historians before him, Ross discovered that it’s a difficult story to tell outside the pages of a 700-page book. Ideally, The Free State of Jones would have been a multiple-season HBO series. Entire episodes could have been spent highlighting the racial tensions between the white defectors and runaway slaves in Knight’s camp. Instead of one tussle over a black man eating some rotisserie pork, the complex, rapidly-changing dynamics around race could have been treated with the nuance they deserved. During Reconstruction, the trauma of lost promises could have been treated in more than a one-scene discussion of Andrew Johnson’s policy of restoration. This didn’t happen.

Nonetheless, for the future of Reconstruction Era history-telling, The Free State of Jones leaves room for hope. It is heartening that critical reviewers have called the film a “noble failure.” If the effort is noble, that means more will try. When they do, they can borrow one strategy of Ross’s that, I’d argue, did work well: a strategy of building composite characters to express the gravity of historical change. One example is Lieutenant Barbour, a recurring antagonist of Knight’s who quickly assumes a role as a prominent judge right after the war. Built from several different people the real-life Knight encountered, this character illustrated the frustrating speed with which racist, slavocratic business-as-usual resumed the moment war ended. A more powerful composite character is Moses Washington (played by Mahershala Ali), a fictional escaped slave with a storyline drawn together from the known histories of thousands of freedpeople in the postbellum South. At times a more “real” character than even Knight, Moses emerged as the chief protagonist of the Reconstruction Era portion of the movie, elucidating the crucial role black men and women played in fighting for their own rights and liberties after the war.

When the war ended, The Free State of Jones was no longer about Knight or his rebellion. It became about his efforts to assist freedpeople in a struggle that was, too often, entirely their own. Knight became a lonely ally in someone else’s story. The story of Moses—and the many real people he represented—needs to be told on its own terms. Hopefully, other filmmakers will see the vast potential in Ross’s effort and follow his lead.

Michael J. Steudeman is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Rhetoric

at the University of Memphis